The Boxer indemnity scholarship program

"The future of China depends on the quality of the men who are receiving their education. These now come mostly to the United States, there being a thousand such students here, and the Institute is the favorite place for those desiring scientific training."

FT Yeh (MIT Class of 1914, Naval Architecture), The Tech, March 26, 1914

In May 1908, following negotiations with the Chinese government, the U.S. Congress passed a bill that enabled the establishment of a scholarship program for the education of Chinese students in American colleges and universities. The bill provided for a return of a portion of the Boxer Indemnity owed by China to the US as reparations for losses incurred during the anti-foreign Boxer Uprising of 1900-01. The original bond having exceeded actual US damages, the bill reduced the indemnity from $24,448,778.81 to $13,655,492.69 (plus interest). The Chinese government agreed to use the money to send students to the US, and for the establishment of a Chinese Educational Mission office in Washington, DC. The initiative thus funded thereby came to be known as the Boxer Indemnity Scholarship Program. Supporters of this program had urged President Roosevelt to approve the initiative as a gesture of friendship to China, and also as a means of solidifying American influence over the new generation of Chinese leaders. As University of Illinois President Edmund James wrote in a letter to President Theodore Roosevelt in 1906:

"China is upon the verge of a revolution...The nation which succeeds in educating the young Chinese of the present generation will be the nation which for a given expenditure of effort will reap the largest possible returns in moral, intellectual and commercial influence.”

In light of the urgency of China's modernization and national defense in this era, the government agreement stipulated that Boxer Indemnity Scholarship students should focus on the fields of science, engineering, agriculture, medicine and commerce. MIT was thus a natural choice for many, as highlighted in the comments by FT Yeh quoted above. The Indemnity Fund also provided partial scholarships for self-supporting students already in the US, provided they study technical subjects. Thus government policy influenced the turn away from humanities toward STEM fields.

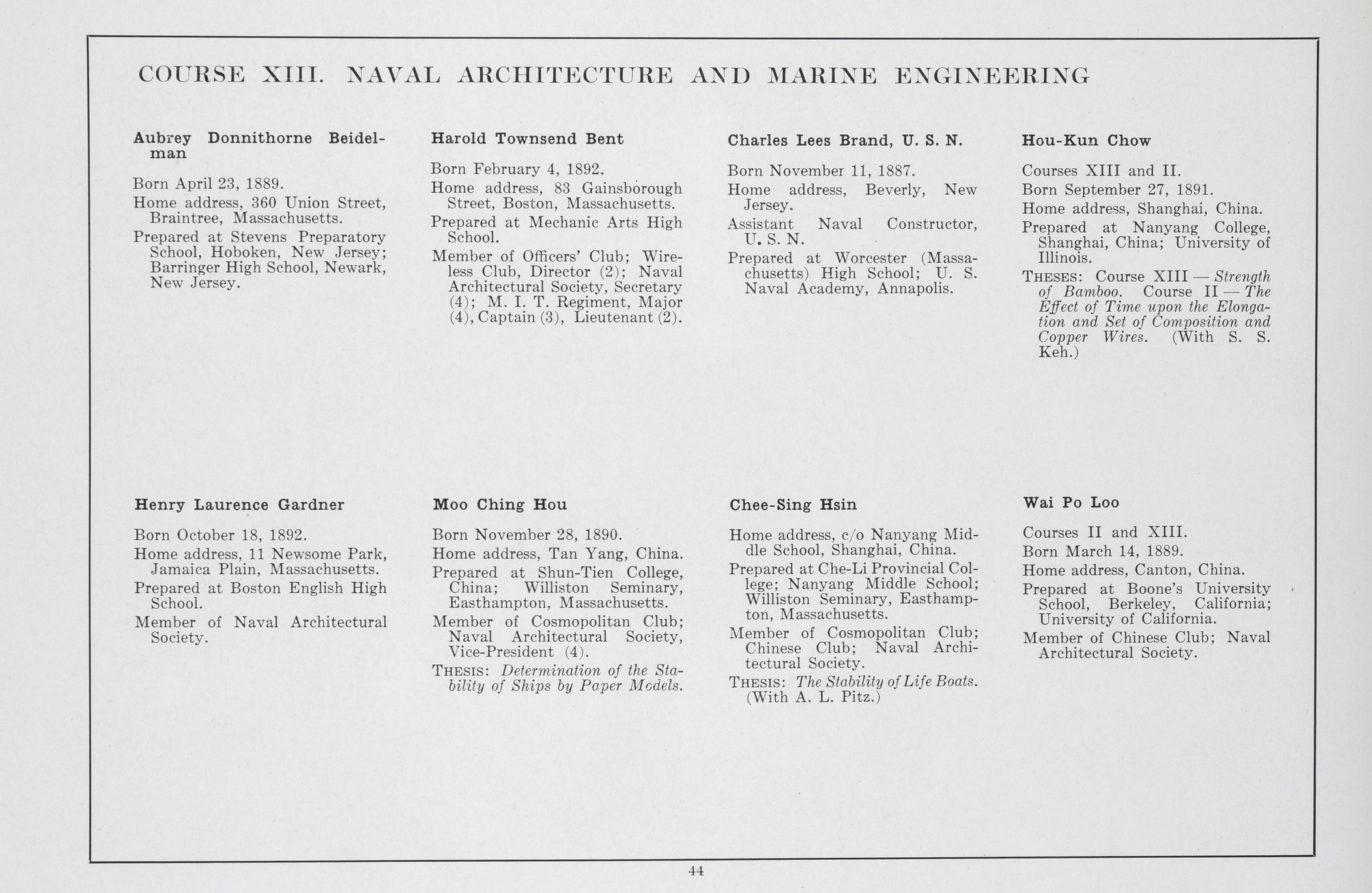

Beginning in 1909, the Boxer Indemnity Scholarship Program sent a steady stream of students, selected through a rigorous examination process, to study in the US before the program was interrupted by the Japanese invasion of China in 1937. Drawing candidates from across China, the examination for this prestigious scholarship was highly competitive: out of 630 candidates for the first examination of 1909, only 47 were selected. Thirteen of the 1909 cohort of Boxer Indemnity Scholarship students attended MIT, the largest number for any single American institution. The students were: Chang Tsun 張準 (Class of 1915, Chemistry) #6 in above photo; Chen Hwang 陳晃 (Class of 1915, Chemistry, BS, MS) #17; Chen King Yaon 陳慶堯 (Class of 1914, Chemistry) #19; Chen Shao Ching 陳兆貞 (Class of 1914, Civil Engineering) #13; Hou Moo Ching 賀懋慶 (Class of 1914, Naval Architecture) #8; Hsin Chee Sing 邢契莘 (Class of 1914, Naval Architecture BS, MS) #29; Hsu Pei (Paul) Hwang 徐佩璜 (Class of 1914, Chemistry) #38; Loo Wai Gyiao 羅惠僑 (Class of 1913, Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering, BS, MS) #18; Tai Shui Tao 戴修陶 (Class of 1916, Mechanical Engineering) #20; Tseng Chou Chuan 曾昭權 (Class of 1915, Electrical Engineering) #5; Van Yung Tsun 范永增 (Class of 1914, Sanitary Engineering BS, MS) #34; Wu Yu Ling 吳玉麟 (Class of 1913, Electrical Engineering BS, MS) #28 and Yuan Tsang Kyien 袁鍾銓 (Class of 1915 Electrical Engineering [received his BS degree from University of Colorado in 1916]) #37. In contrast to the earlier Chinese Educational Mission (CEM), which was heavily dominated by students from Guangdong Province, the students in the Boxer Indemnity Scholarship Program hailed from across China.*

As noted by Zouyue Wang, despite their diverse backgrounds the Indemnity students shared "a dream of saving China through science and technology." (2002, 292) Many of these students went on to become the founders of modern chemistry, chemical engineering, electrical engineering, mechanical engineering, naval architecture, physics, and other fields back home in China.

Provincial origins of MIT's 1909 Indemnity Scholars. Google Maps.

Boston residences of MIT's 1909 Indemnity Scholars. MIT was at this point located in Boston's Back Bay.

Kuang Piao Hu, Technique 1920. Image Courtesy MIT Archives and Special Collections.

Following in the footsteps of the CEM students, some of the first Boxer Indemnity Scholarship students initially attended New England preparatory schools before entering university. MC Hou, CS Hsin, Paul Hwang Hsu, WG Loo and YL Wu, for example, were among a group of students who arrived in the US in October (missing the fall entrance exams) and thus spent a year at Williston Seminary prior to matriculating at MIT in 1910. Arriving with strong foundations in English as well as math and science, the Chinese students flourished at Williston, several winning prizes in debating and oration. The students wrote senior theses on topics ranging from Chinese civilization to educational reform in China and the need for modern railways.

Tsinghua University, Class of 1926. Image courtesy David Chang.

In 1911, a special batch of 14 "junior scholars" was selected to attend American preparatory schools on Indemnity scholarships. Owing to financial problems, their departure was delayed until 1914, and their number reduced to 11. Among these students, Huang Chi Yen of Guangdong (Class of 1919, Civil Engineering) came to MIT from Phillips Academy Andover, and Hu Kuang Piao of Sichuan (Class of 1919, Electrical Engineering) and Li Kuo Chou of Guangdong (Class of 1921, Mechanical Engineering) from Phillips Academy Exeter.

In order to prepare students directly for college studies in America, the Tsinghua School in Beijing was established in 1911 as the Boxer Indemnity Scholarship Program’s official preparatory school. In 1929, the Tsinghua School officially became Tsinghua University. Since these early years, when Tsinghua sent a steady stream of students to MIT, there has been a special link between the Institute and Tsinghua, which has sometimes been called the "Chinese MIT."

The Indemnity scholars contributed to a dramatic increase in the number of Chinese students at MIT: from 11 in 1909, to 27 in 1910, 36 in 1911, and 42 in 1913. As HS Hsin wrote in a story for the Technique, out of the 42 that year, all except five self-supporting students were government-scholarship students. This is quite unusual given that in 1910, only roughly 1/3 of Chinese students in the US held government scholarships. In 1914, MIT celebrated the graduation of 17 Chinese students from MIT – the largest number to date – a historic occasion also featured in newspapers in China. Ten of these students were Indemnity Scholars, two held Navy scholarships, one held a partial government scholarship, and four were self-supporting.

The influx of students attracted much attention in Boston, and the Boston Post noted that a "veritable colony" of Chinese MIT students had grown up on St. Botolph Street in Boston. It also brought good publicity to the Institute as the place where future leaders of China were being trained. As the Boston Sunday Post declared on November 6, 1910:

MIT Senior Portfolio 1914. 6 Chinese students received degrees in Course XIII that year. Image courtesy MIT Archives and Special Collections.

The hopes of the "New China," the rejuvenated nation that perhaps is to do all and more with western ideas than did Japan, are centered for the present on the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where more than a score of the most promising young men of the empire are being educated for places in the government service and particularly in the Navy. ("Tech Training of Chinese Group May Mark the Birth of New Regime in Far East")**

These hopes for a New China were raised even higher after the Chinese Revolution of 1911 and the establishment of a new Chinese Republic.

The critical mass of Chinese students entering the US during this era enabled the founding of several professional societies, including the Science Society of China, the Chinese Engineering Society, the Chemical Society of China, the Chinese Society of Naval Architecture, and others, which initially had their headquarters in the US but relocated to China as the founding students returned home. As might be expected, MIT students were early leaders in these science and engineering societies. Along with YR Chao of Cornell, MC Hou (MIT Class of 1914) led the way in an important initiative among the overseas students to translate scientific and technical terms into Chinese, using a "group method."

The Boxer Indemnity Scholarship Program, which has been called one of the most significant educational initiatives of the 20c, dramatically boosted the number of Chinese students at MIT, and established a firm tie between the Institute and China.

From John Fryer, Admission of Chinese Students to American Colleges, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1909.

Notes: According to MIT's policy in 1909:

It is interesting to note that in 1909, 33.9% of Chinese students in the US studied engineering, and only 16.4% humanities, but by 1931 this had evened out to 22.4% and 20.8%, respectively. Bieler, Stacey. "Patriots" or "Traitors"?: A History of American-Educated Chinese Students. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 389. On distribution of courses in 1921, see this link.

*Chang Tsun went on to become one of the most important pioneers of modern chemistry in China and also an expert on the history of science. Chen Hwang was a leader in the field of industrial chemistry, who held various governmental and academic posts. Chen King Yaon served in the Beijing-Shanghai Railway Bureau. Chen Shao Ching also worked for the Railways and taught at Jiaotong University. Hou Moo Ching was a leader in his student years and went on to serve various government posts in China. Loo Wai Gyiao served as Technical Supervisor at the Jiangnan Shipyard, and held various government and academic positions, including Head of the Chinese Air Force office for Burma and India during World War II. Hsin Chee Sing was another leader among the students, and made numerous vital contributions to naval engineering, aeronautics and hydraulics in China. Hsu Pei Hwang was a leader in the field of industrial chemistry and applied chemistry education. Tai Shui Tao made numerous contributions to shipbuilding and navigation. Tseng Chou Chuan was a pioneer of electrical engineering. Wu Yu Ling helped establish some of China's first electric power plants and serve various government positions. TK Yuan became a middle school teacher.

**It should be noted that this enthusiasm was not universally shared in China, where some considered Western-educated "returned students" to be arrogant, lacking in patriotism, and ignorant of actual conditions in China.

Sources: Mary Timmins, "Enter the Dragon," University of Illinois alumni website, https://illinoisalumni.org/2011/12/15/enter-the-dragon/, The Tech, March 26, 1914, 3, Bieler, Stacey. "Patriots" or "Traitors"?: A History of American-Educated Chinese Students. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, The Tech, March 18, 1908, volume XXVII, no. 59, “Chinese Students Arrive,” Boston Daily Globe, Sept. 13, 1911, p. 4, The Lowell Sun, November 16, 1910, "A Benefit from Boxer Reimbursement," Boston Post, September 17, 1909, 8, "47 Chinese students coming to America," Boston Post, September 16, 1909, 5, Chinese Students' Alliance in the United States of America, The Chinese Students' Directory, January, 1914, Boston, 1914, CY Wang, Chinese Intellectuals in the West, 1872-1949, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1966, 151, Wang, Zuoyue. "Saving China through Science: The Science Society of China, Scientific Nationalism, and Civil Society in Republican China." Osiris 2nd Series 17 (2002): 291-322, "Tech Training of Chinese Group May Mark the Birth of New Regime in Far East," Boston Sunday Post, November 6, 1910, "Future Admirals and Master Builders of Chinese Navy Are Trained at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology,” Boston Sunday Post, April 27, 1913, 10, “Chinese Students Entertain.” Technology Review v. 16, n. 9, Dec. 1914, p. 683, “Chinese Tech Students Win,” Technology Review v. 17, n. 8, Nov. 1915, p. 633, MIT Senior Class Portfolio 1914, The Technique 1910-1917, Paul Hwang Hsu, "The Williston Chinese," The Williston Bulletin, Volume 2, No. 1, October 1916, 7-10, Senior Theses, Williston Academy, Williston-Northampton Academy Archives, CS Hsin, "The Chinese Student at Tech," Technique 1915, 13-14, Who's Who of American Returned Students (You Mei tongxue lu), Beijing: Tsinghua College, 1917, Who's Who of the Chinese Students in America. Berkeley, Calif: Lederer, Street & Zeus company, 1921, China Institute in America. A Survey of Chinese Students in American Universities and Colleges in the Past One Hundred Years. In Commemoration of the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Graduation of the First Chinese from an American University, Yung Wing, B.A., Yale 1854. A Prelim. Report. 1954, MIT Chinese Students Directory: For the Past Fifty Years, 1931, “Publicity in China: How our Chinese Students Are Helping to Make Technology Known in Their Native Land.” Technology Review v. 16, n. 8, Nov. 1914, pp. 564-566, The Chinese Students Monthly, 5.8 (June 1910), 529, Jiaoyu zhi qiao: cong Qinghua dao Mashengligong/Bridge of Education: From Tsinghua to MIT. Hong Kong: Cosmos Point Limited, 2011, Chinese Students' Monthly, 10.6 (April 1915): 453-454, Kirby, William C. "Engineering China: The Origins of the Chinese Developmental State." In Becoming Chinese, edited by Wen-hsin Yeh, 137–160. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

For more information see the Boxer Indemnity Scholars blog.

![Boxer Indemnity Scholarship Recipients 1909. See page for author [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57bdab71e3df28e77a3cf28e/1474638335040-PWBZU2FPZ92NW6NQRCCH/image-asset.jpeg)