z.z. li 李善述

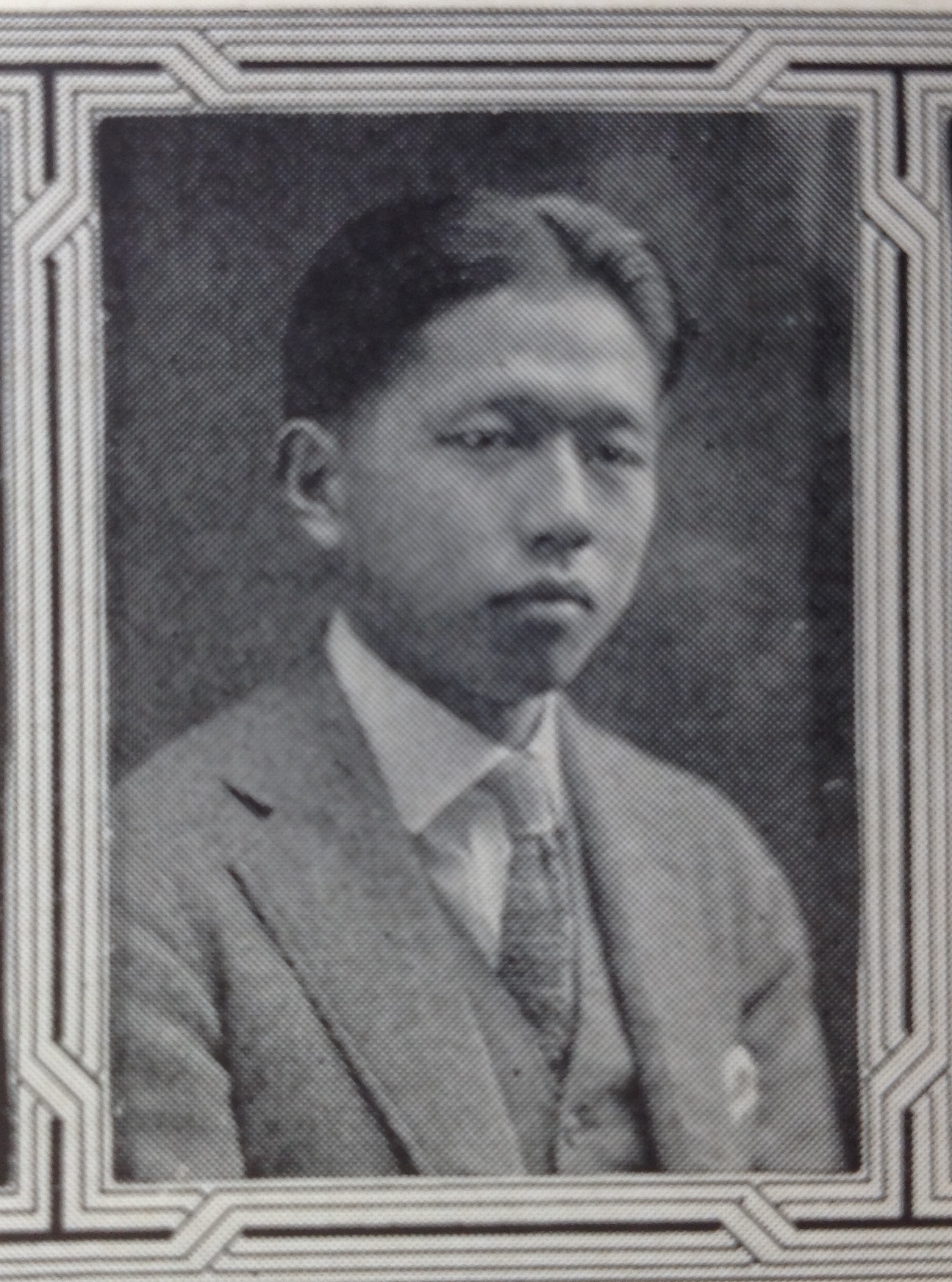

ZZ Li, Technique 1923. Courtesy MIT Archives and Special Collections.

Zen Zuh Li (Class of 1922, Chemical Engineering), was born in Zhejiang province and prepared at St. John’s University in Shanghai before matriculating at MIT. Li came to MIT with two other friends from his hometown, Nanxun, all the sons of important local families from this historic hub for the silk trade. Li entered MIT in the second semester of his freshman year, but finished in two and a half short years, graduating in 1922. During his student years, Li was active in several student organizations, including the Chemical Engineering Society, the Cosmopolitan Club, and the Chinese Students’ Club, for which he served as Treasurer in his senior year. Working under the direction of Prof. R. T. Haslam, Li wrote his thesis on the topic of “Paper Pulp from Chinese Bamboo by the Soda Process.” In this thesis, Li described traditional Chinese methods for making paper from bamboo, and investigated modern methods, with experimentation on the soda process using samples of bamboo brought in from China. Li perceptively predicted that “bamboo seems destined to hold an increasingly important place as a raw material for paper.” The insights from this research would be put to good use after Li returned to China, bringing his penchant for innovation to his work as a paper engineer. In the year following graduation, he spent some time in Maine, training in paper mill engineering at the Eastern Manufacturing Company, and traveled in Massachusetts and Wisconsin, doing site visits to various paper mills. Although Li worked briefly in paper engineering, it was in the silk industry where he made his mark. Working in the import-export sector, during the war years (1937-1945) Li played an important role helping ensure China’s continued ability to trade with foreign countries. At the Fu Hwa Trading Company in Hong Kong, he became head of the tea department, handling large-scale barter shipments to Russia. Later, at the Universal Trading Corporation in New York, he was in charge of the sale of Chinese tung [wood] oil, conducted in order to repay the loan of $25 million extended the company by the Export-Import Bank of Washington in 1938 to facilitate the export of American goods to China and the import of Chinese tung oil. The loan had been made as a form of support to China in the war against Japan. At the Universal Trading Corporation, Li rose to the position of assistant vice-president in charge of the purchase of war materials and equipment for China. Hence, Li made vital contributions to China’s wartime survival. Always dedicated to his alma mater, in 1938, Li hosted the fourth monthly meeting of the MIT Club in Hong Kong along with fellow Nanxun native, Zhang Jiuxiang (Class of 1923). An accomplished painter and poet, Li published several literary works in his later years. The following is an account of his life written by his youngest daughter, Lillian.

ZEN ZUH LI (1899-2000), MIT CLASS OF 1922: FROM ENGINEER TO ARTIST AND POET

Z. Z. Li portrait, ca. 1950. Courtesy Lillian Li.

early years

My father, Zen Zuh Li 李善述, or Li Shanshu in Mandarin, was also known by his literary-name (hao), Shu Chu 述初. In the West, he was usually called Z. Z. by his friends and associates. He was born on October 18, 1899, in Nanxun (or Nanzing), a canal town in Wuxing, Zhejiang province. The Li family had lived in this town for three centuries, and established a kind of gentry-merchant life that might today be called upper middle-class. My grandfather Li Yuren, (Li Yeu-zung) had a classical education and received the first Imperial degree of xiucai, but also participated in the antique export trade, based at first in Paris and later in New York. In the 1920s, he started a silk export company.

My father also had a traditional early education in Nanxun, but later attended St. John’s in Shanghai, an American Episcopalian boarding school and college. There he enjoyed instruction that was in both Chinese and English. Many St John’s graduates assumed leadership roles in government, business, and higher education in the Republican period (1912-1949) of Chinese history, and formed important networks that continued after 1949 outside of China.

In his family life, my father was guided by traditional Chinese values as well as by modern Westernized customs. His marriage in 1919 to my mother, Soong-jen Fong 方松琴 (1900-1991), had been arranged since their infancies by their two fathers who had known each other for years. My mother’s family was more conservative than my father’s; for example, she never received any schooling outside of the home and her feet were bound as a child (but unbound after a few years). Their first child, a daughter, was born soon after the marriage, just shortly before my father departed for his MIT education in the US, leaving my mother to live with his parents, in the manner of traditional Chinese households.

Document issued by the Foreign Affairs Office of the Chinese government certifying Zen Zuh Li’s student status, Oct. 21, 1919. Images in this row courtesy Lillian Li.

Zen Zuh Li’s Chinese Certificate, Oct. 21, 1919. This document was issued to my father to enable him to study at MIT. It states that he was “a member of one of the exempt classes described in” the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 (as amended in 1884).

This snapshot shows four young men, three from Nanxun, aboard the SS Nanking, bound for the US in fall 1919. My father is on the left. Pau Ting KWE (second from left) and Jiuxiang ZHANG (right), friends from Nanxun, also attended MIT.

Zen Zuh Li at MIT, ca. 1922. Photo courtesy Lillian Li.

MIT years

My father entered MIT in 1920 and graduated in 1922 with a B.S. in Chemical Engineering. Although he was very proud of having attended MIT, I do not recall his ever telling me any details of his school life there. I know he lived in a boarding house in Boston and ate a lot of baked beans!

Here is my father in line for an MIT event. He seems a bit unhappy and looks like he is begging for alms with his straw hat!

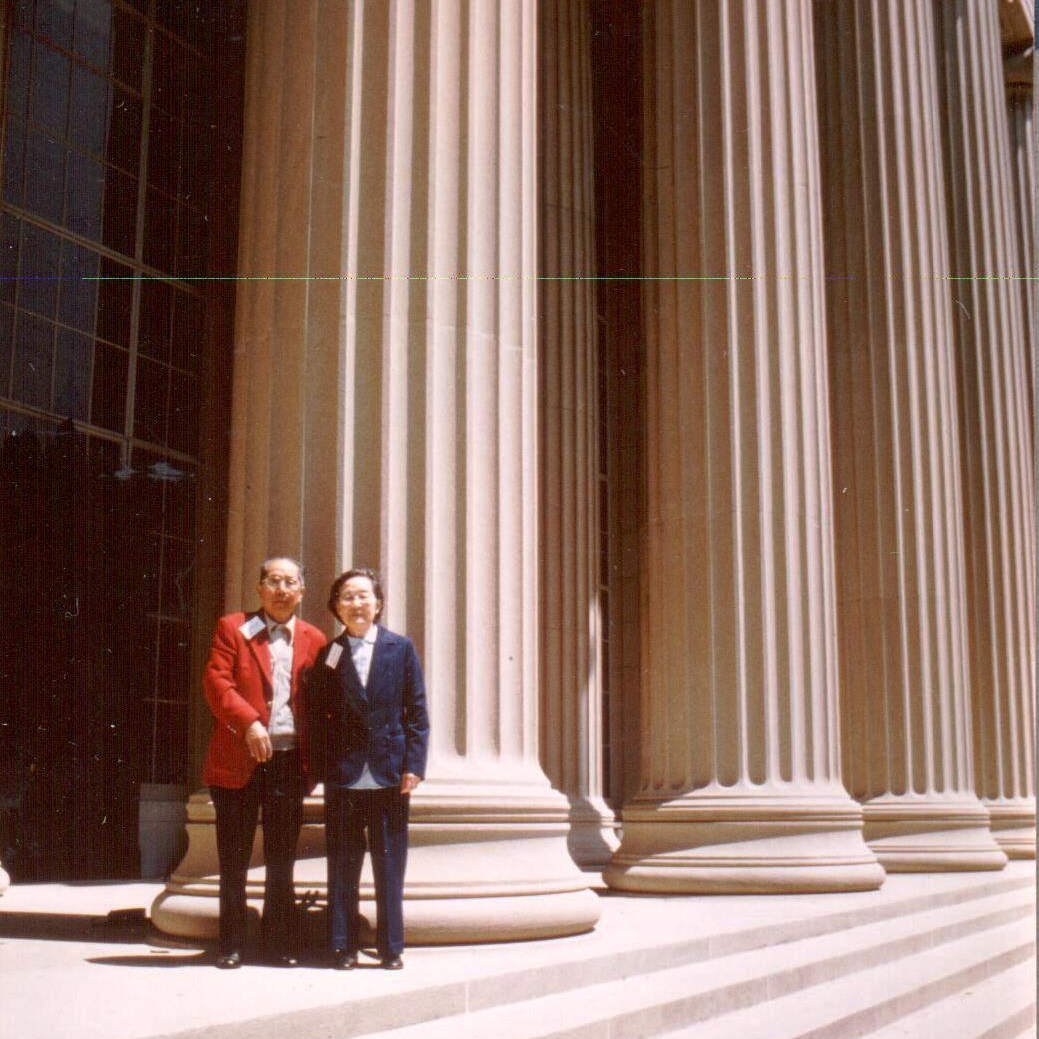

In 1982, my father was thrilled to attend his 60th class reunion, proudly decked out in his red MIT reunion blazer. He even decided to give a speech!

MIT Class of 1922 60th Reunion photos, 1982, courtesy MIT Museum and Lillian Li.

engineer and family man

After graduation, my father returned to China, and worked as the paper engineer successively with two paper mills located on the outskirts of Shanghai. This was the only time he was employed specifically as an engineer. After that he worked with his father’s Tonying Silk Trading Company: first stationed in New York to supervise the direct sale of raw silk to American mills, and later in China as manager of the company.

From 1935 to 1936, my father served as Secretary of the Sericulture and Raw Silk Commission of the National Economic Council of the Chinese government and as Sales Department Manager of the Chekiang Raw Silk Sales Committee. In this connection, he travelled to New York, London, Lyons, Zurich and Milan to survey world silk markets.

From 1937 onward he worked for the Chinese government’s Foreign Trade Commission, facilitating Chinese trade during the war with Japanese. In 1938-39, he served in Hong Kong with the Fu Hua Trading Company, established to facilitate Chinese trade bypassing Japanese-occupied Shanghai. By 1939, my father was working in New York for the Universal Trading Corporation, which was an agency of the Chinese government responsible initially for the sale of Chinese wood oil to the US and later for the purchase of war materials and equipment to be supplied to China from the US.

He worked in this capacity until 1956 when the company was dissolved. After that he relocated to Philadelphia to work for the Univac division of the Sperry Rand Corporation in an administrative capacity. After his retirement in 1965, he and my mother returned to New York where they lived for the next thirty years.

The entire family in Shanghai, ca. 1946-7. Courtesy Lillian Li.

This is the only time all seven children were photographed together. The family was about to separate, which is probably why everyone looks rather somber.

My parents had six children while living in China, mostly in Shanghai. All six were educated in missionary-established schools. During my father’s frequent trips overseas, my mother raised them in the family home, first in Nanxun and later in Shanghai. In 1941, my father suggested that she accompany him to NY since she had never travelled abroad, and the children, now ranging in age from twenty-two to ten, could be looked after by relatives. After the Pearl Harbor attack, however, they were not able to return to Shanghai and remained in New York until the end of the war, separated from their children. During that time, they had me, their seventh child.

In 1946, they returned to Shanghai and decided to move permanently to the US, taking the older 3 children and leaving the middle 3 to finish their schooling in Shanghai. The Chinese Communist revolution of 1949 prevented these three from joining us in the US: so two sons and one daughter grew to maturity in China with hardly any contact with the family. After 1949, such family separations were common among my parents’ relatives and friends.

Zen Zuh Li 50th Birthday Party, New York, 1949. Courtesy Lillian Li.

In New York during the 1940s and 1950s onward, there were a great many Chinese families like ours, who had come to the US for their education or business and remained to escape Communist rule. So my parents had a wide circle of friends and acquaintances, mostly from Shanghai, with whom they socialized. Most like my father were engineers, but others followed professions such as medicine, or became businessmen.

My father was a member of the Phi Lambda fraternity, a Chinese American social organization. P. L. Brothers offered mutual support and family-centered activities, especially at an annual summer “convention” in some outdoor setting. Friendship was very important to my father, who was quite outgoing and always ready to help friends in need, and, in turn, to accept their help when needed.

This photograph of my father's 50th birthday shows that Shanghai could be re-created in New York. My parents are seated in the first row, third and fourth from the left. I, my oldest sister Pearl, and my second sister Ellen are on the floor, second, third, and fourth from the left.

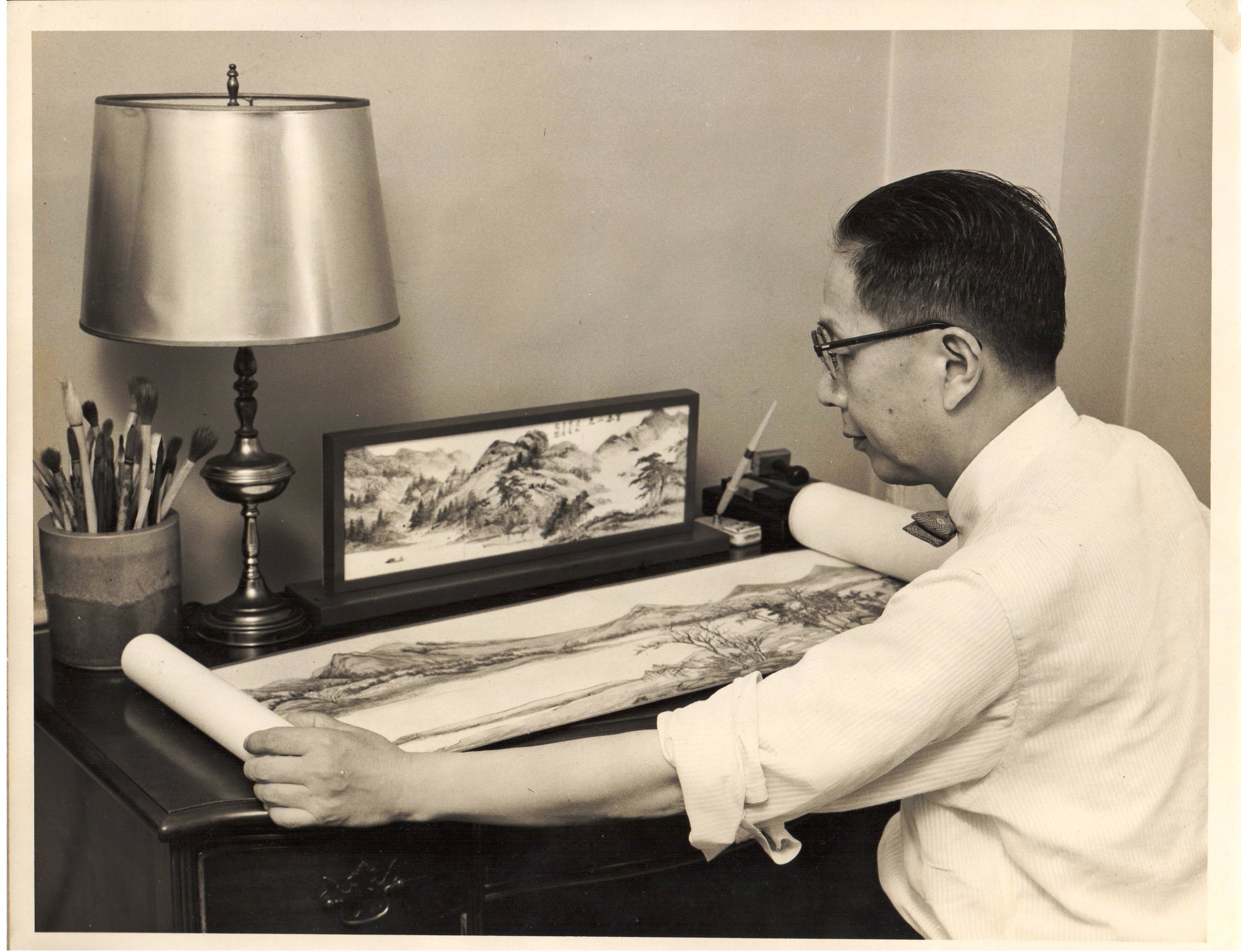

Zen Zuh Li, painting at home, 1960s. Courtesy Lillian Li.

ARTIST and poet

More than anything else my father loved painting and poetry. He started to paint in the 1940s, painting traditional Chinese landscape and bamboo. In New York, he studied with CC Wang, a well-known painter, calligrapher, and collector, who was also a good friend. He also studied with artists in Taiwan and from Taiwan. In addition to these professional artists, my father exchanged paintings and poems with like-minded friends, for whom composing a poem or painting scrolls of bamboo or landscape was not just for one’s own pleasure, but also to exchange among friends -- just like the Chinese scholars of the past. Many of these valued friends had also been trained as engineers, but in their older years began to draw on their classical Chinese education and become modern-day literati. (Y. H. Ku, MIT Class of 1925, was one such friend.)

"Spring in Kiangnan." Card produced and sold at MIT Museum at the time of the painting exhibit. Courtesy Lillian Li.

After his retirement my father became even more productive as an artist. In addition to his painting, he loved to compose poems and eventually published a few volumes of poetry as well as a family memoir.

"Zen Zuh Li '22: Painter and Poet," exhibit at the MIT Museum, 1983. Image courtesy MIT Museum.

His paintings were exhibited in New York, Philadelphia, and Taipei. In 1983, the MIT Museum hosted an exhibition of his paintings, which was a joyous occasion that allowed my father to bring together his artistic passion and his engineering background.

[The title of the MIT Museum exhibit was "Zen Zuh Li '22: Painter and Poet, Paintings in the Traditional Chinese Style." Click here for a poem written by ZZ Li on the occasion of viewing the exhibit.]

___________________________________________________________

Three-century Man

Another source of pleasure for my father was reuniting with his three children who had been left in Shanghai in 1947 and meeting his grandchildren for the first time. Starting in the late 1970s, it was possible for Chinese Americans to return to China to visit their relatives, and in the 1980s, each of my three siblings was able to visit the United States on different occasions. My father was fortunate to have a large gathering of friends and relatives on his eightieth birthday, and to have two celebrations of his ninetieth birthday, one in Beiiing and another in New York.

After my mother died in 1991, my father continued to live in New York, but starting in the mid ‘90s, he lived with my second sister Ellen in New Jersey, and later with me in Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, and finally at a retirement home in nearby Media, Pennsylvania.

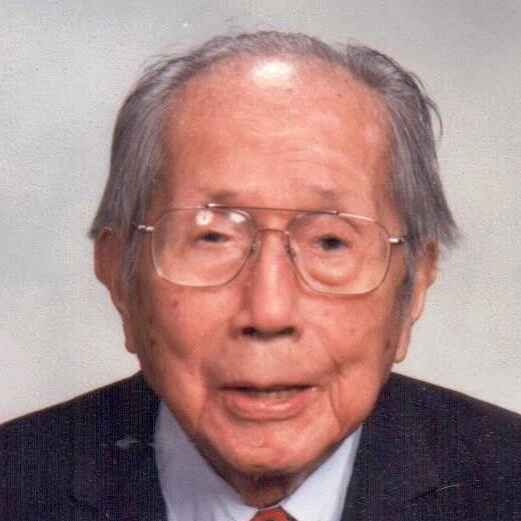

Someone had once told my father that since he had been born in 1899, he might become a “three-century man” by living until the 2000s. He reached that goal, passing away on February 26, 2000, just months after celebrating his 100th birthday on October 18, 1999 (see photos below).

Photos: 1. Christmas reunion of daughters, 1981. Daughter Yunzhu (rear left) from Beijing visited New York during her research year at University of California, Davis.

2. Zen Zuh Li 90th Birthday in New York. This photo shows my parents with their eldest son Richard (on the right), and their eldest grandson Roger (on far left) and younger grandson Ronald (second left). The MIT reunion blazer was re-purposed for this occasion: red being auspicious.

3. Zen Zuh Li, 100th birthday celebration, Media, Pa.

4. Zen Zuh Li, One-hundredth birthday portrait.

Photo essay by Lillian M. Li, November 21, 2016.

Notes: Zen Zuh Li's Chinese literary works include the following: 李述初詩稿 (1966), 晨光集 (1971), 李述初詩畫集 (1978), 李述初詩稿續集 (1982), 李述初米壽紀念冊, Zen Zuh Li -- Through 88 Years (1987).

Sources: MIT Technique 1923, Li, Zen Zuh. Paper Pulp from Chinese Bamboo by the Soda Process. 1922, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, MIT Chinese Students Directory: For the Past Fifty Years, 1931, MIT Museum files, "Zen Zuh Li '22: Painter and Poet, Paintings in the Traditional Chinese Style," exhibit, 1983, Ta Kung Pao, Nov. 10, 1938., Trundle, Sidney A. History of the Export-Import Bank of Washington, Box 14, Folder 7, William McChesney Martin, Jr., Papers, accessed on December 5, 2016, Li, Zen Z. Painter and Poet: Paintings in the Traditional Chinese Style. Cambridge, MA: MIT Museum, 1983, 李述初米壽紀念冊 (Zen Zuh Li -- Through 88 Years). 1987. Patricia Wen, "The lost liberal arts university of China," Boston Globe, March 3, 2012, "Li, Zen Zuh," New York Times obituary, Feb. 29, 2000. Lillian Li, email correspondence, November-December, 2016.