bringing china to "tech"

“No, Tse [Tsok Kai] never worked in a laundry; he’s a real mandarin from Canton. You will hope that they’ll never let him back to the Celestial region after he does his turn. Here’s where you do the kow-tow." (MITTechnique, 1908)

Wedding picture of Yang-Mo Kuo (Class of 1917, MS 1919) and Wai-Tsu New (of Radcliffe) in 1918. Left to right in the back: Mary R. Cabot, Grace Cabot Holbrook, Grace Ware Holbrook Haskell, Reverend W Dewees Roberts. Courtesy of Veronica Haskell (granddaughter-in-law of Grace Haskell). (See Kuo profile.)

The students had been sent from China with the mission of learning Western science and technology, but in Cambridge they found themselves taking on a role that was perhaps equally important for China's future: that of cultural ambassador. This was an era of pervasive anti-Chinese sentiment, especially on the West coast, but also a time of burgeoning interest in the Far East – its cultures and markets. With its longstanding connections to the China trade, Boston was a leader in this vogue and birthplace of "Boston Orientalism." Against this backdrop, the Chinese students attempted to promote understanding of China and its people, often drawing on its great heritage of arts, culture, and philosophy to assert the equality of Chinese and Western civilizations, despite the latter's recent rapid advances in science and technology.

Appealing to the community’s curiosity about China, as well as emerging ideals of cosmopolitanism, the students organized various public events and also worked through person-to-person contacts to achieve this goal. Frequently excelling in their studies and earning the respect of their teachers and peers, the Chinese students left a deep impression on the MIT community, and helped advance Sino-American friendship.

Cultural ambassadors

Autograph of Pah Liang Fong (Class of 1884), 1875. Courtesy Williston Northampton School Archives. Fong quotes a line from Mencius:

"Humaneness is the human heart, and righteousness the path. To abandon the path and not follow it… Alas!"

On March 1, 1910, a group of forty students at MIT formed the Cosmopolitan Club, with the aim of promoting world citizenship and offering support to international students. Eight Chinese students joined this club, and Heenan Tinching Shen (Class of 1909, Naval Architecture) was elected Second Vice-President, serving alongside officers representing Norway, Ecuador, the US, France, and the Canal Zone.

Tsok Kai Tse's note to graduates in the Technique 1906. Courtesy MIT Archives.

In April 1910, the Chinese members of the Cosmopolitan Club hosted an entertainment at the Club rooms at 480 Boylston Street, with thirty-six members in attendance, including faculty. The program opened with two speeches: the first on Chinese intercourse with the West, and the second on the traditional Chinese educational system. This was followed by a performance of Chinese music by two students, lantern slides, stories, phonograph music, and a trivia quiz on China. Several faculty won prizes for correctly answering questions such as: "what is the total area of China in square miles?" The prizes were Chinese ornaments.

This launched what would become the annual "Chinese Night," which by 1912 attracted an audience of more than 300 for an event jointly hosted with Harvard. With HK Chow presiding, the Chinese students not only entertained the audience of students and faculty with performances of music, pantomimes, card tricks, and demonstrations of the Chinese game of shuttlecock, but also discussed current political conditions in China with the founding of the new Republic. In subsequent years, a wide variety of topics were discussed, and Chinese Night became an important venue for educating the MIT community about Chinese customs, history, philosophy, and current events. Chinese food was also served, to the delight of the participants.

Beyond MIT, the Chinese students received invitations to speak at clubs and churches in Cambridge and Boston, and even in the surrounding suburbs. Many Americans were eager to collect souvenirs, such as autographs, from their Chinese acquaintances. The editors of MIT's Technique 1906 asked T. K Tse (Class of 1908) to provide this note for the yearbook, translated below:

"A Short Account of Boston Tech"

Boston Technology Institute was founded in 1860 (sic) by Dr. William [Barton] Rogers, et alia. The university specializes in the study of science. There are 6 professors’ buildings. Although I matriculated not long ago, I have seen that the level of its course of study is really the top among American universities. Now, the path of technology prizes results above all: to learn theorizing (mens) alone is nothing more than "discussing soldiers on paper," but Boston Tech takes practice (manus) as its motto. I wish to congratulate all the gentlemen of this university for their bright futures.

the chinese fete

Chinese Night was only one of the collaborative endeavors undertaken by the Chinese students with their counterparts at other local universities. On April 24, 1914, Chinese students at MIT, Harvard, Wellesley and other Boston-area schools put on a "Chinese Fete” at the Copley Society of Boston. With hundreds of Bostonians in attendance, the students performed a dramatic interpretation of the classic Chinese novel Journey to the West under the title of "A Pilgrim's Progress." MIT students were prominent in this production as actors, musicians and on the production crew. MC Hou played the lead role of The Monkey and Turpin Hsi the supporting role of The Monk of the Desert. Hou Kun Chow played The Ox Demon, CC Tseng the Demon of Darkness, WG Loo the Emperor, FT Yeh the Leopard, and T Yuan the Tiger. Techun Hsi, T Chang, CS Hsin, L Lau and ZY Chow were also involved. Miss Mayling Soong of Wellesley (the future wife of Chiang Kai-shek and First Lady of the Republic of China) was an assistant producer. Livingston Platt designed the stage set. Indicative of the vogue for Orientalism among upper-class Bostonians of the time – not only the players, but also the spectators wore Chinese costumes to the Fete. The Boston Globe called the event "one of the most charming pictures in costuming and scenery imaginable." The play was so successful that it was repeated the following year, with essentially the same cast.

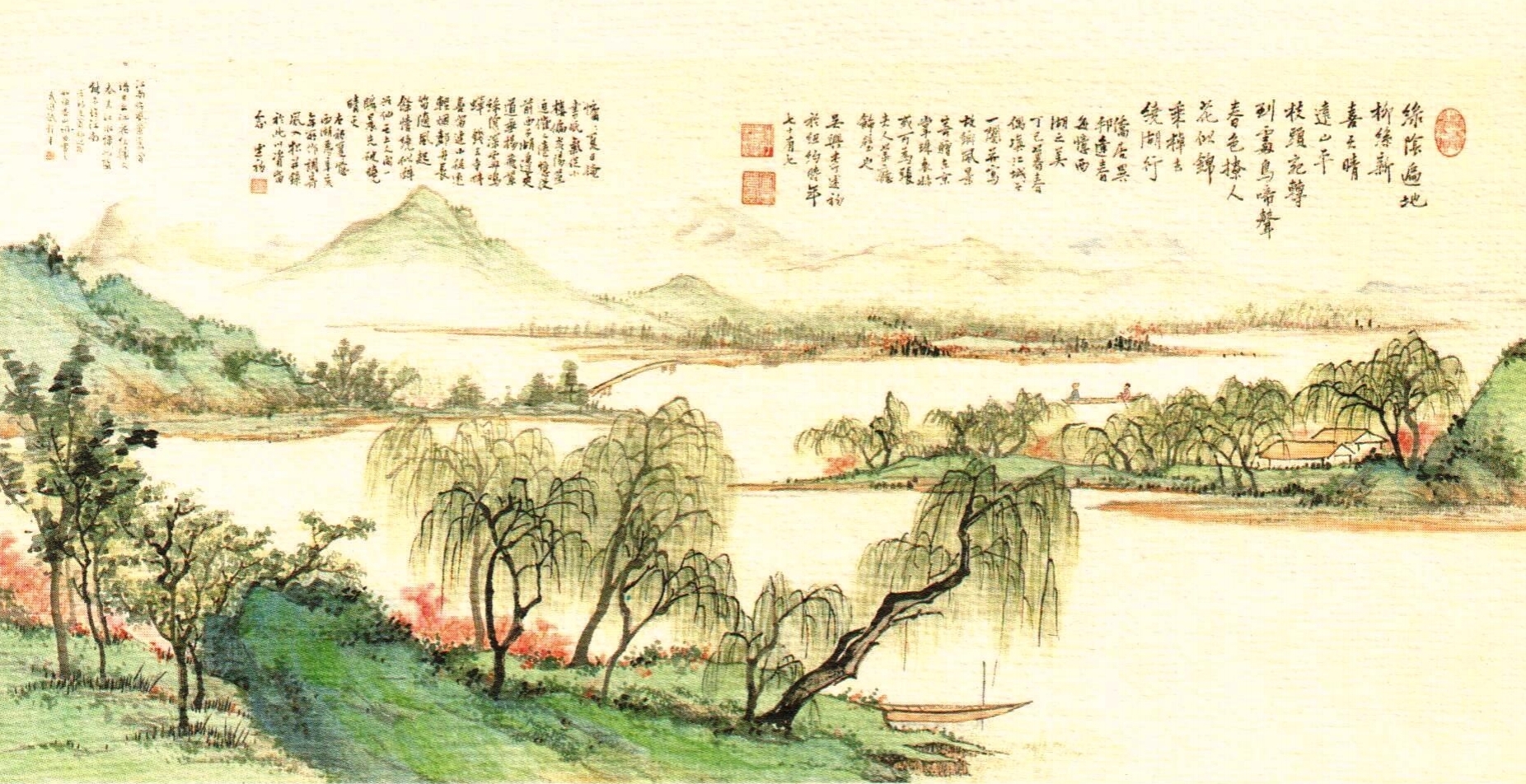

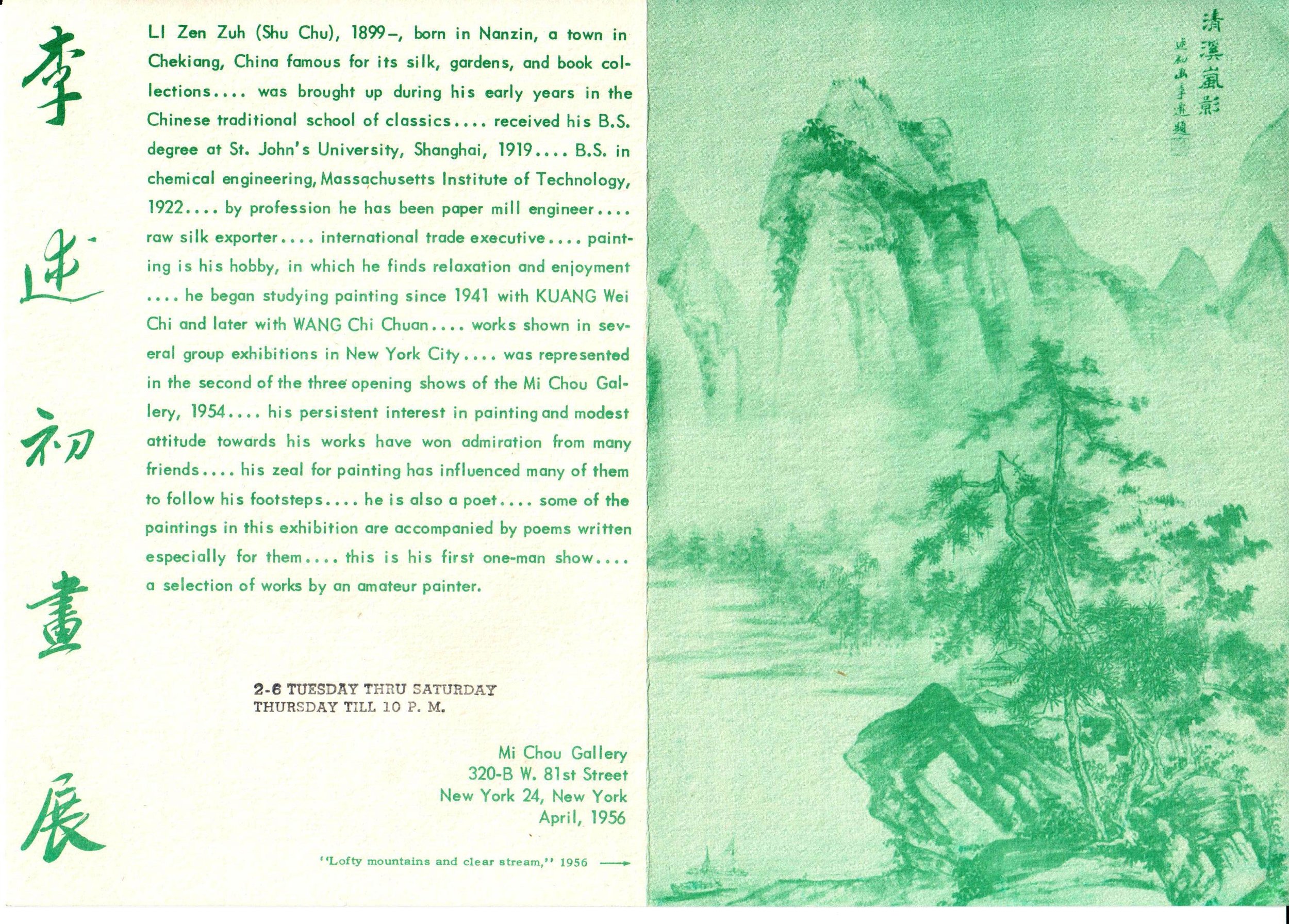

Painting by Z.Z. Li (Class of 1922). Image Courtesy Lillian Li.

In 1925, the Chinese Students of Greater Boston put on another major production, an English spoken-drama version of the popular Ming dynasty Chinese theatrical work, "Pi Pa Chi" (The Story of the Lute) written by MIT student Ku Yu Hsiu (Class of 1925, Electrical Engineering, MS 1926, DSc, 1928) and translated by Liang Shiqiu. The play was performed at the Fine Arts Theater in Boston on March 28 and 29, 1925, with Grace Zia of Wellesley College playing the heroine. As advertised in the Harvard Crimson:

"The Chinese students attending institutions in greater Boston will produce a play entitled ‘Pi Pa Chi’ at the Fine Arts Theatre next Saturday night. The play will be in English. It was written by Kou Ming, a prominent Chinese scholar of the fourteenth century."

According to Liang's memoirs, over 1000 people attended the play, and the "roof was almost shaken off by the stormy applause."

Qu Zengfa (屈曾發) comp, The Comprehensive Examination of Mathematics (Jiushu tongkao), 1772, 1898 reprint. Courtesy MIT Libraries.

LITERARY BRIDGES AND TRANSLATION

To further their project of educating Americans about China, and also to maintain their own connection to the homeland, the Chinese Students’ Club, founded 1910, made several book donations to the MIT Libraries. The first major donation occurred in 1912-1913, soon after the founding of the Republic of China. The gift consisted of “216 volumes in Chinese, comprising the History of the Dynasties, 200 volumes; The Abridged Chronology from 2000 B.C. to the beginning of the Christian Era, eight volumes; and four other books.” A later donation in 1923 consisted of twenty volumes of Chinese literature and thirty lantern slides. The maintenance of this "Chinese Shelf” in the Institute Central Library, with copies of the Chinese classics – the Confucian "Four Books" and "Five Classics" -- in addition to current newspapers, periodicals and books from China, was a central mission of the club.

Interactions with the Chinese students inspired numerous faculty and students to take a keen interest in China and Chinese culture. While many went to China to pursue opportunities in business, engineering, teaching or the military, perhaps the most interesting example of an individual who developed an abiding interest in studying Chinese culture is Tenney L. Davis (Class of 1913). A professor of organic chemistry, Davis was interested in the history of chemistry and alchemy and became curious about Chinese alchemy. Working together with chemistry student Lu-Ch’iang Wu ((Class of 1928, Chemical Engineering, Sc. D. 1931), Davis translated the classic Chinese text The Kinship of the Three (Cantong qi), the earliest extant Chinese text on alchemy, publishing the translation in 1932. With Wu and other Chinese students, Davis continued to work on other classic Chinese alchemy and Taoist texts, publishing articles throughout the 1930s and 1940s. These collaborations produced some of the earliest English translations of important Chinese texts, and were seminal contributions to the history of science and technology in China. Nathan Sivin credits these translations with initiating Western "consciousness of the Chinese alchemical tradition."

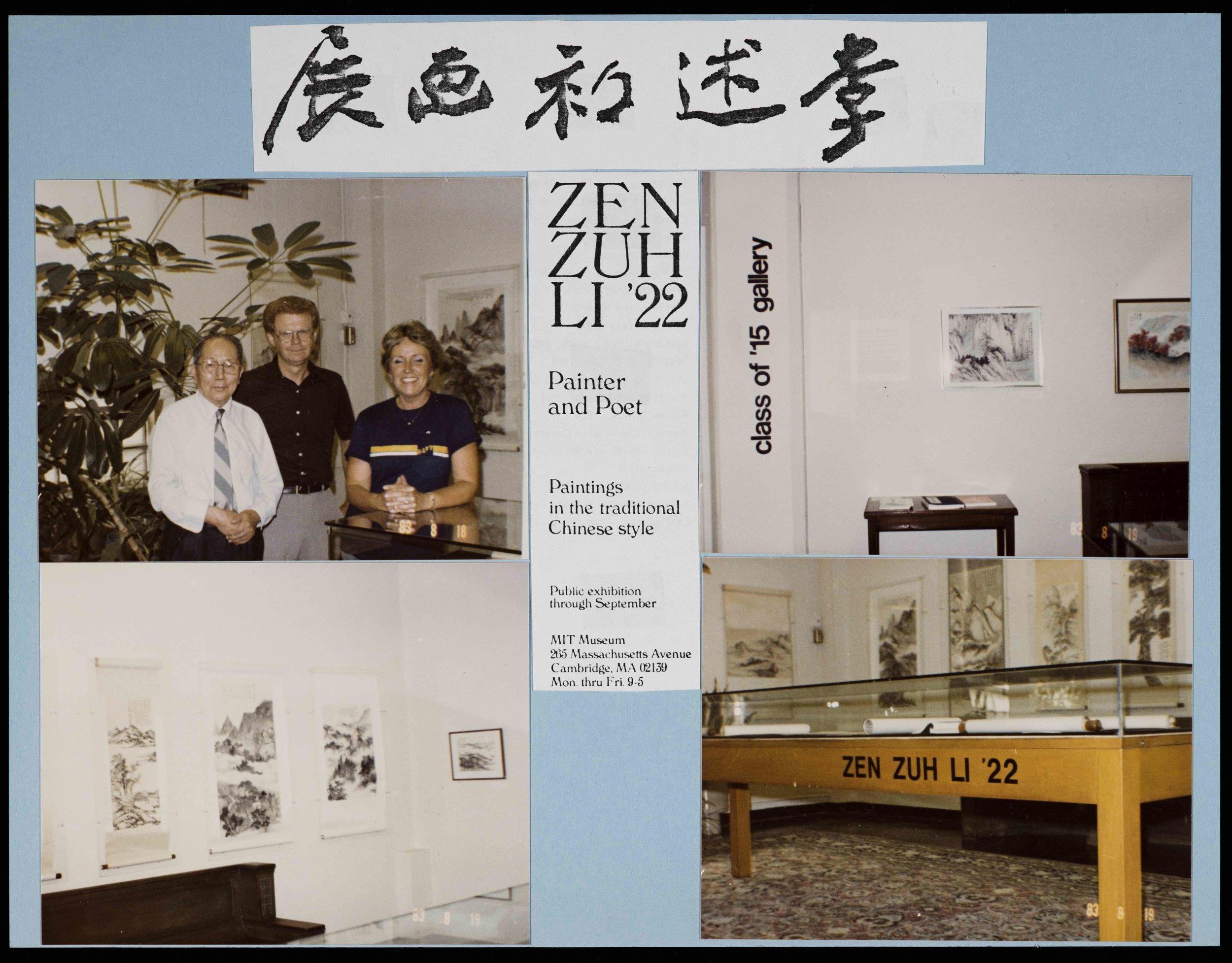

"Zen Zuh Li '22: Painter and Poet, Paintings in the Traditional Chinese Style." Courtesy MIT Museum.

Artistic gifts

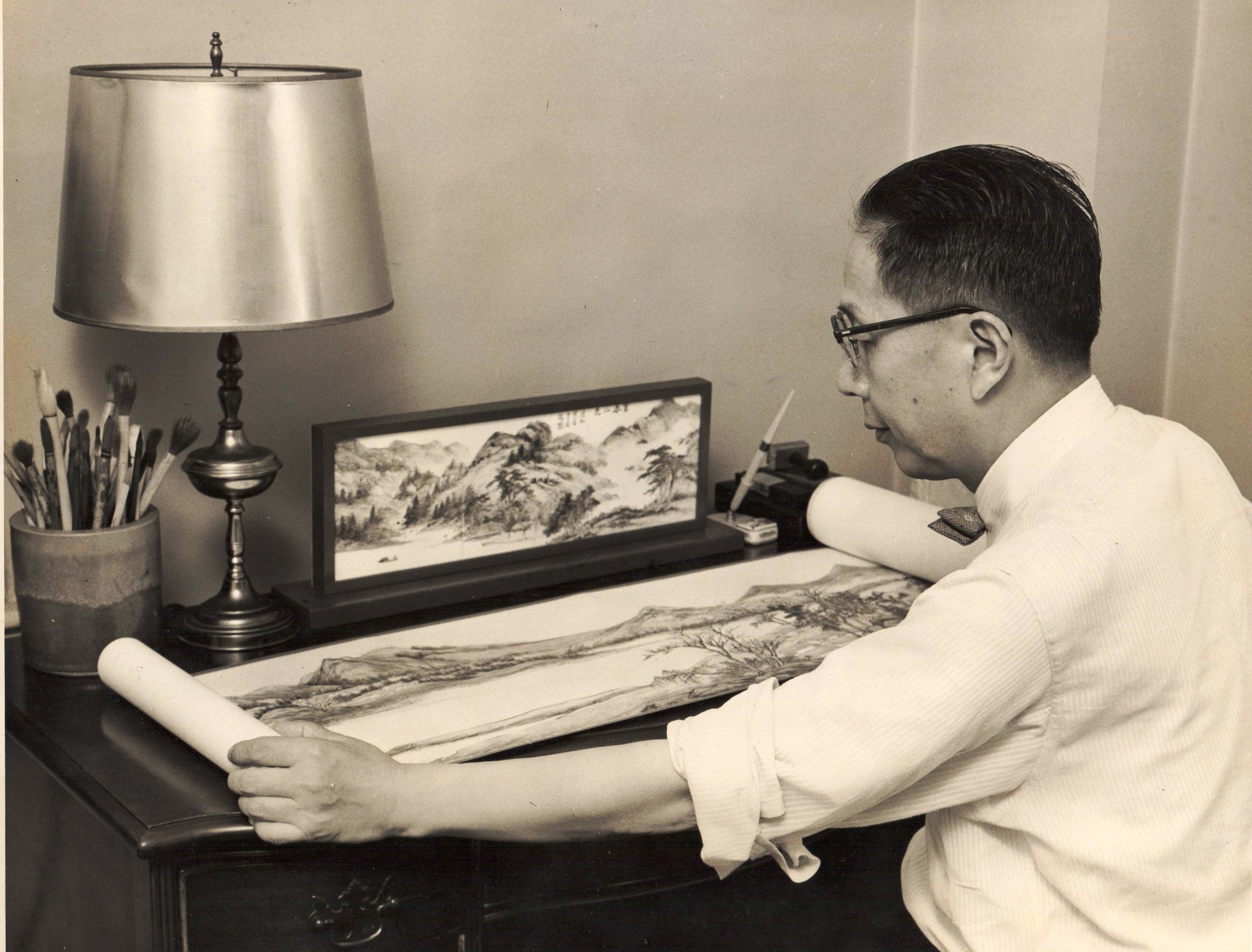

Artistic talent was another gift the Chinese students had to share with the MIT community. Zen Zuh Li (Class of 1922), for example, trained as an engineer, but discovered a true passion for the linked Chinese arts of ink painting, calligraphy and poetry later in life. In 1983, the MIT Museum hosted a public exhibition of his paintings, "Zen Zuh Li '22: Painter and Poet, Paintings in the Traditional Chinese Style." At the close of the exhibition, Li donated three paintings to the museum's permanent collection, as well as copies of his poetry and memoir. Reflecting on the experience of revisiting MIT in old age and viewing his own exhibit, Li wrote a poem in the traditional Chinese style, musing that:

"Art and science come from the same source." (Click here for full poem.)

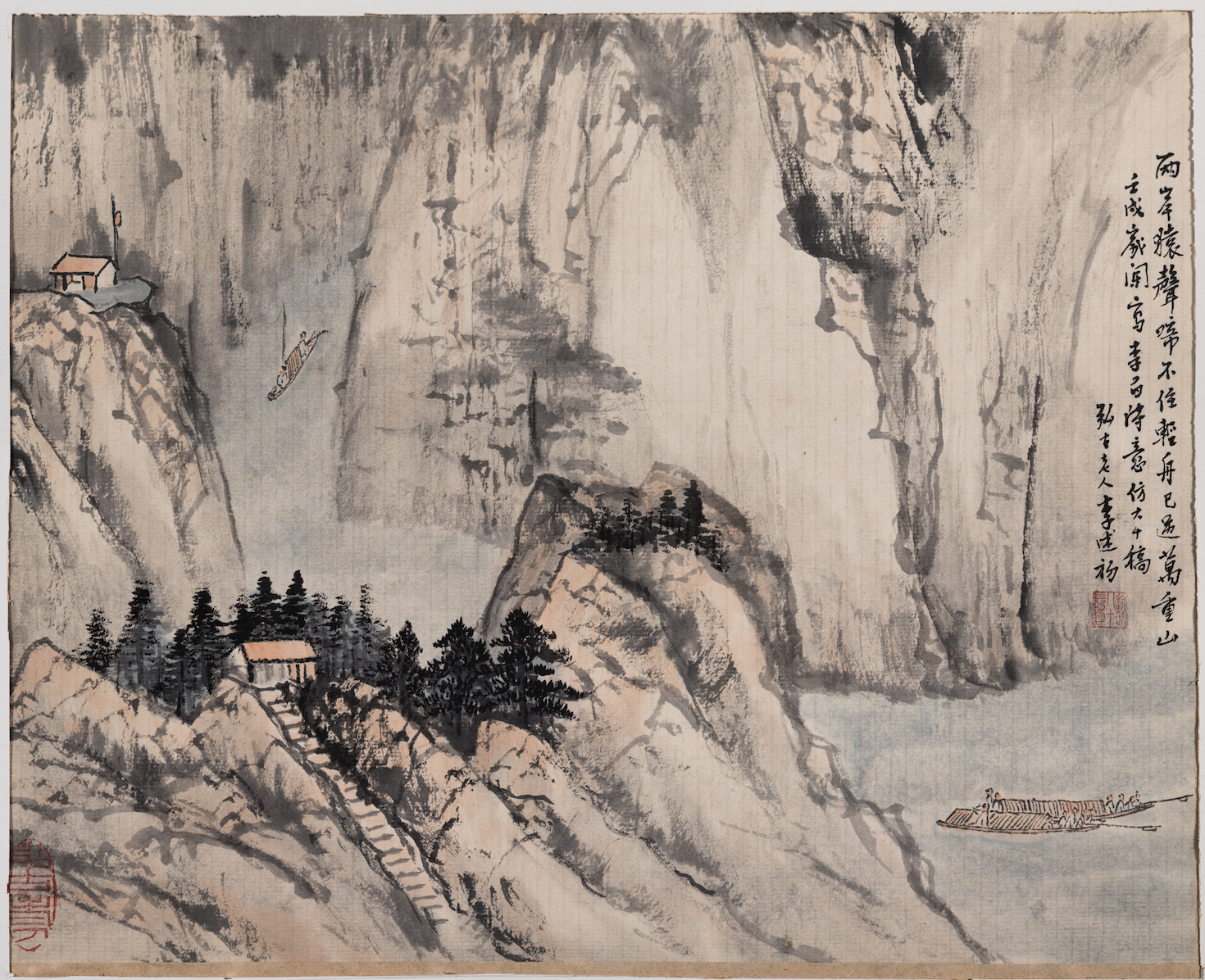

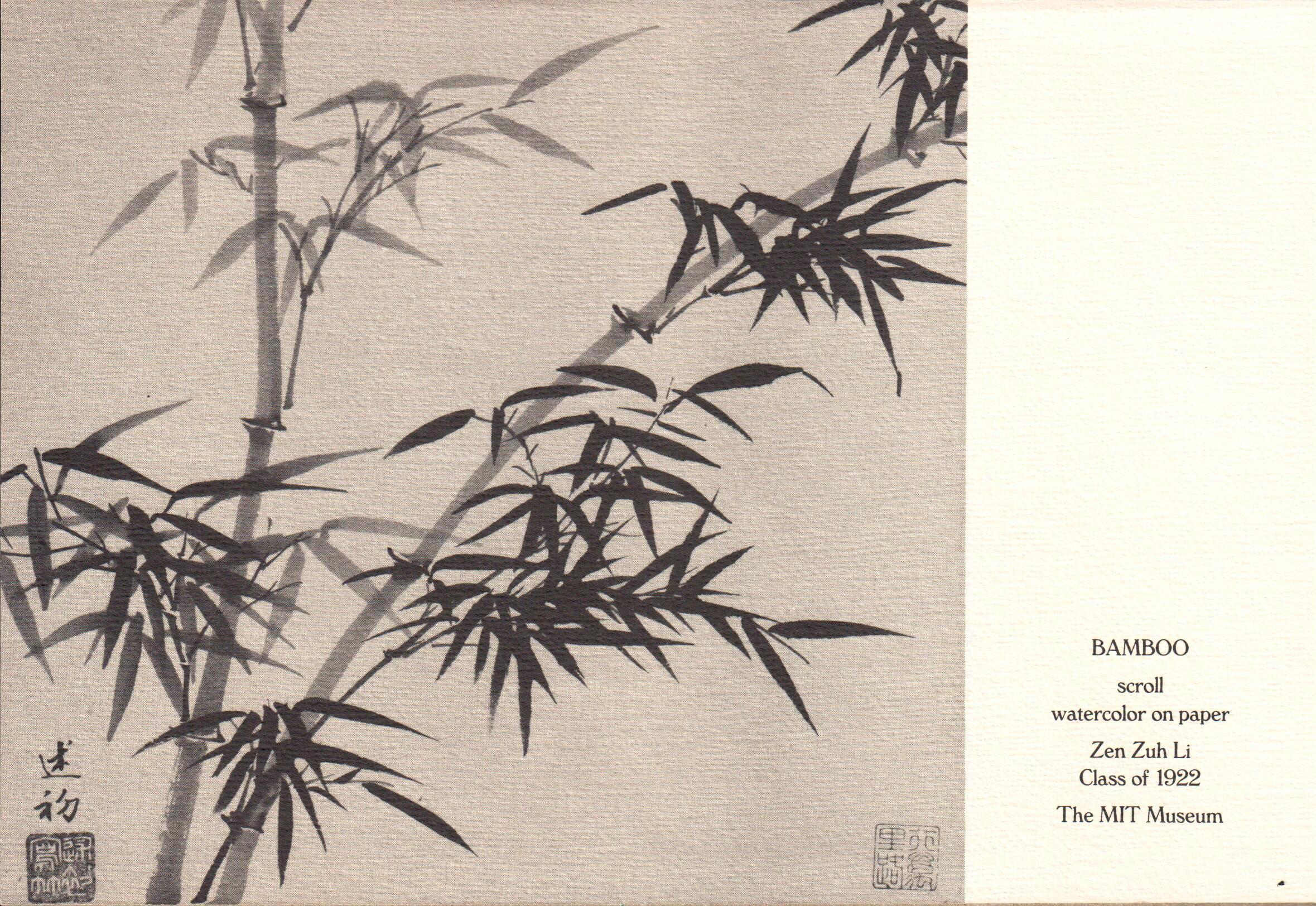

A selection of Li's paintings can be seen below:

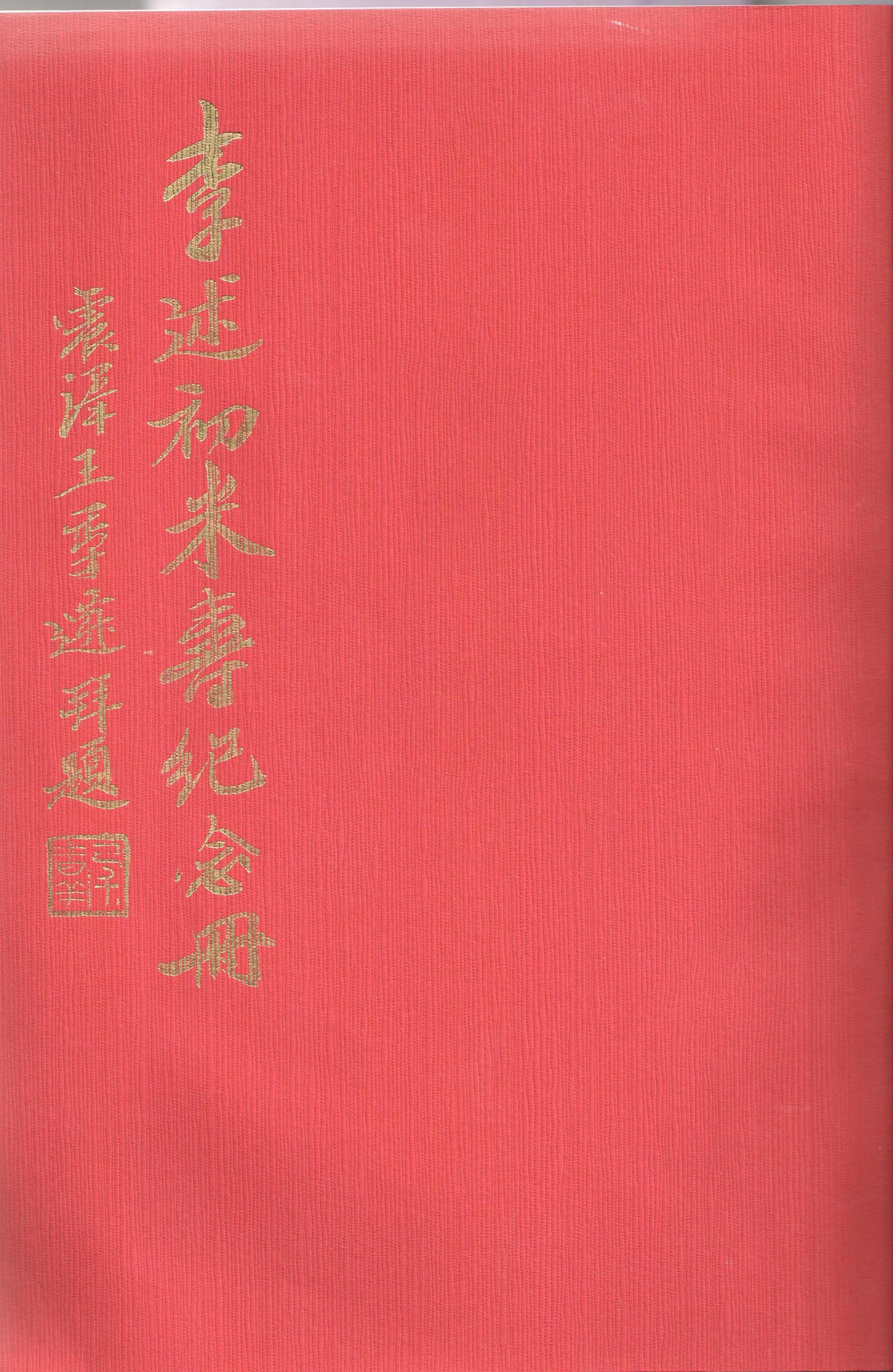

Click to advance carousel. Zen Zuh Li "Through the Yangtze Gorges," courtesy MIT Museum. Zen Zuh Li, "Spring in Kiangnan," courtesy Lillian Li. Zen Zuh Li, "Bamboo," courtesy Lillian Li. Mi Chou Gallery brochure, courtesy Lillian Li. Zen Zuh Li painting at home, 1960s, courtesy Lillian Li. Zen Zuh Li showing new painting to his wife, SJ, courtesy Lillian Li. Cover from 李述初米壽紀念冊, Zen Zuh Li -- Through 88 Years (1987), courtesy Lillian Li.

From the beginning of the overseas educational movement, Chinese students grappled with the question of how they could selectively learn from the West while maintaining their own identity: should they embrace only Western science and technology, while maintaining traditional Chinese values and social or political structures? Was such a dichotomy between "use" and "essence," as one Chinese intellectual formulated it, even possible? Over the years, individual students had very different responses to this dilemma. Yet, we must consider as well the impact of these cross-cultural encounters on the West. Through their efforts as cultural ambassadors, the Chinese students at MIT increased the community's awareness of the rich store of learning and culture that China had to offer America, even as they contributed to the advancement of global science and technology.

*Notes: The Tech, vol XXIX, no. 104, March 2, 1910, The Tech, April 23, 1910, volume XXIX, no. 145, The Tech, volume XXXII, no. 59, December 16, 1912, The Tech, vol. XXXIII, no. 87, November 28, 1913, The Tech, volume XXXIII, no. 89, December 1, 1913, Chinese Students’ Monthly, volume X no.7, May 1914, 562-3. "CHINESE FETE." Boston Daily Globe (1872-1922), Apr 25, 1914, "SETTINGS FOR CHINESE PLAY." Boston Daily Globe (1872-1922), Mar 09, 1915, "Will Repeat Chinese Play." Boston Daily Globe (1872-1922), Mar 08, 1915, "Report of the Librarian," MIT President’s Report, October 1923, 27, Gu, Yiqiao. One Family-Two Worlds, Weili Ye, 2001, 205, The Crimson, March 26, 1925, Liang quoted in Ye 2001, 205, LT Chen, "The American College Man", The Technology Monthly, volume IV, number 6, January 1918, page 25-27, 36. 26, Report of the Librarian, MIT President’s Report, 1913, p. 36, MIT Chinese Students Directory, p 12, Jiaoyu zhi qiao: cong Qinghua dao Mashengligong/Bridge of Education: From Tsinghua to MIT. Hong Kong: Cosmos Point Limited, 2011, 26, Nathan Sivin, “Research on the History of Chinese Alchemy,” 8 in Z. R. W. M. Von Martels ed., Alchemy Revisited: Proceedings of the International Conference on the History of Alchemy at the University of Groningen, 17-19 April 1989.