Chinese Educational Mission at MIT

The pioneering Chinese Educational Mission (CEM) was launched at a time of crisis for China, when the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) was in decline and severely weakened by foreign imperialism. Under this program, the Chinese government sent 120 Chinese youths to live and study in New England, where they were to receive American college educations before returning to contribute to China's modernization and "Self-Strengthening" efforts. The CEM was the brainchild of Yung Wing (1828-1912), the first Chinese student to graduate from an American university (Yale, Class of 1854), and an avid reformer who was:

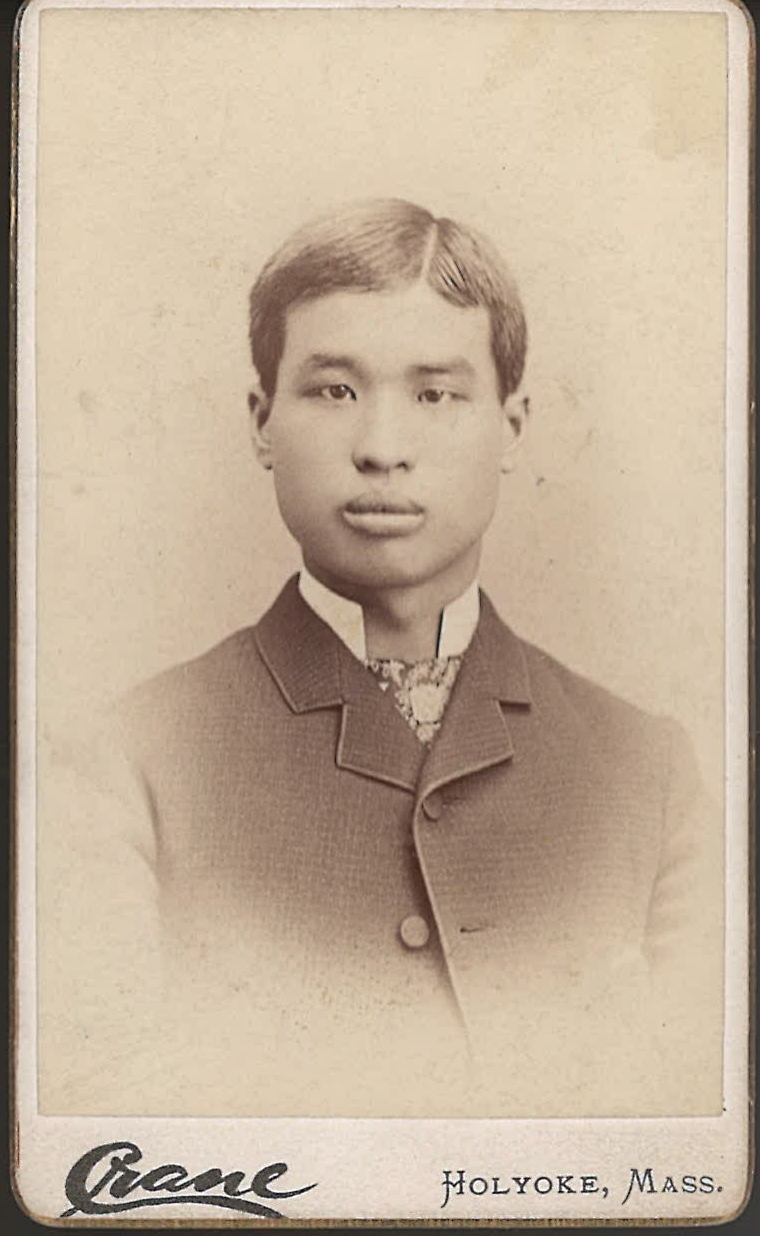

Sik Yau Foke at the Holyoke Public High School ca. 1878. Image courtesy the Holyoke History Room of the Holyoke Public Library, Holyoke, Massachusetts

"determined that the rising generation of China should enjoy the same educational advantages that [he] had enjoyed." (view source)

The first cohort of thirty students arrived in the US in 1872, and boarded with New England host families, many with missionary connections, while they undertook preparatory education at public and private secondary schools. A second detachment arrived in 1873, followed by a third and fourth in 1874 and 1875. The majority of the students hailed from Guangdong Province, with smaller numbers from Fujian Province, Shanghai, and other coastal locations. Progressing through secondary school, the students began entering college, where they elected to study either humanities and social science subjects, or science and engineering. Unfortunately, various factors – including rising anti-Chinese sentiment in the US as well as opposition to the program from conservatives within the Chinese government – led to the abrupt recall of the CEM in 1881, with the students ordered back to China.

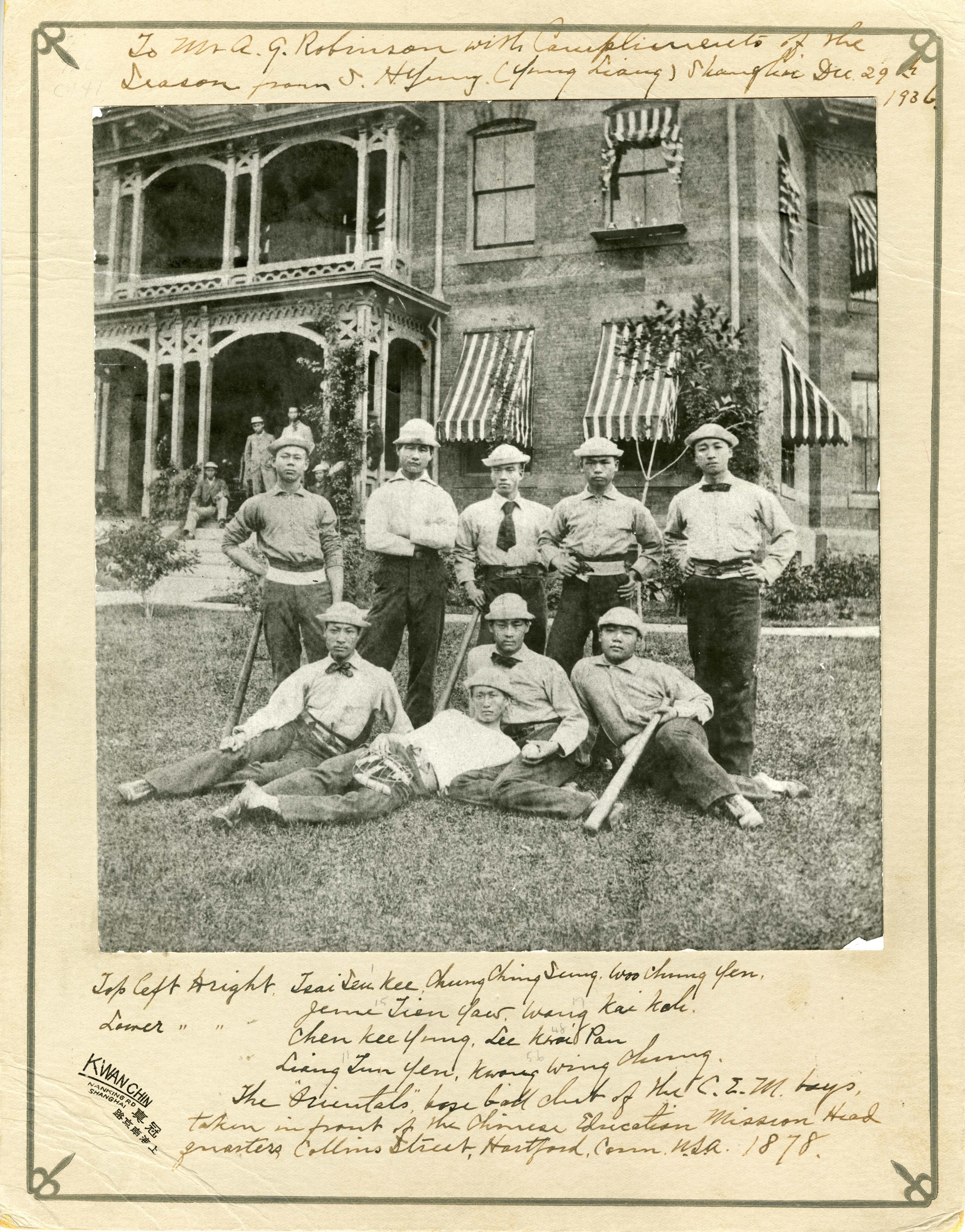

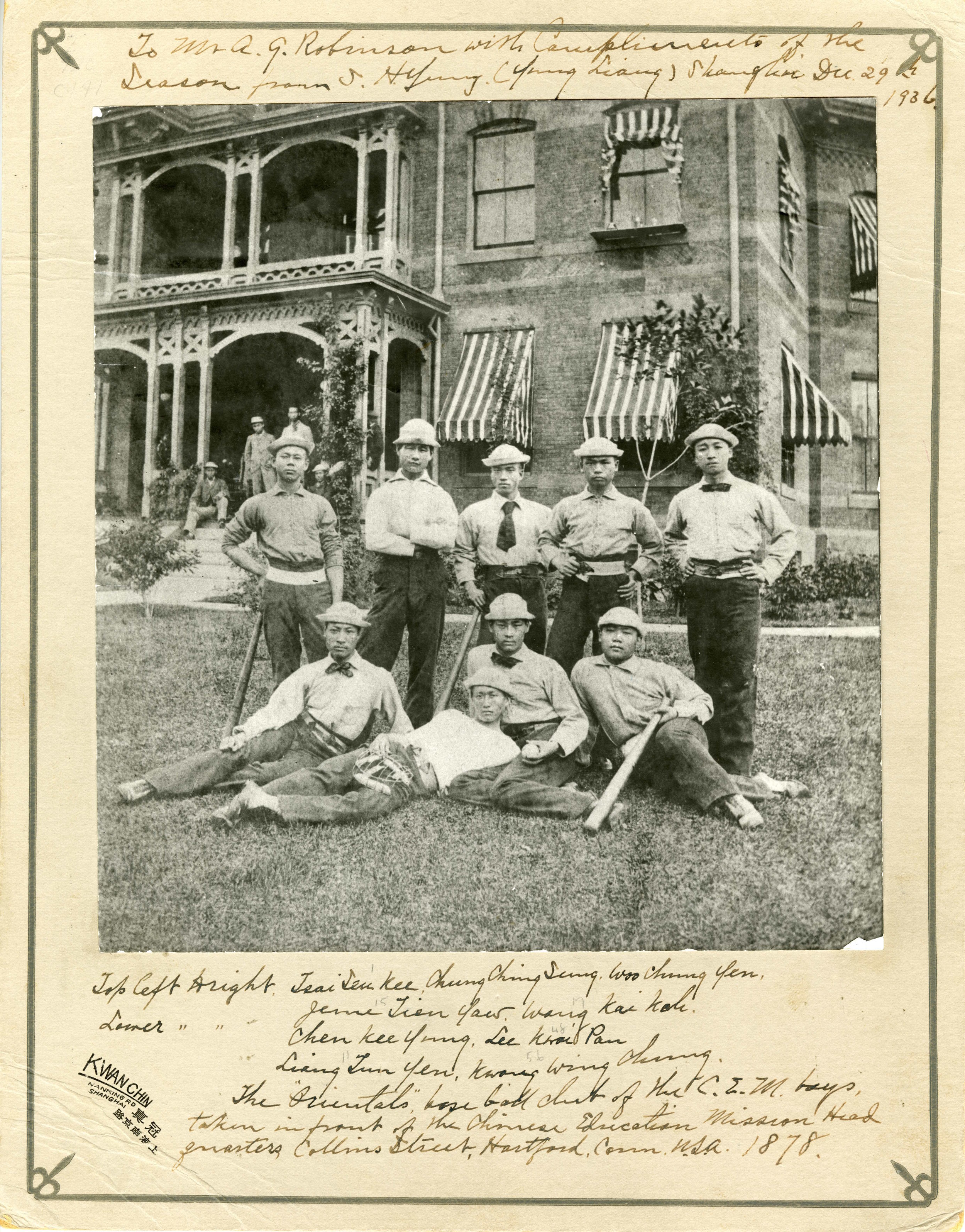

The "Orientals" baseball club of the CEM boys, taken in front of the Chinese Educational Mission Headquarters, Hartford, 1878. 2-1-11, Thomas E. LaFargue Papers, 1873-1946, courtesy Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections (MASC), Washington State University Libraries.

Before the recall, a total of forty-three CEM students had entered college: eight chose MIT, making the Institute the most popular choice behind Yale (which had twenty). These students were: Kwong Yung Chung; Fong Pah Liang; Kwong Hein Chow; Kwong King Yang; Sik Yau Foke; Sung Mun Wai; Tyng Se Chung; and Yang Seu Nam. They came to MIT from various secondary schools, including Williston Seminary, Phillips Academy Andover, the Hartford Public High School, Holyoke High School, and Somerville High School. These eight were among the first Chinese students to study science and engineering in the US. Regrettably, despite a strong letter of protest from the MIT faculty to the Chinese government, the recall of the CEM in 1881 forced the students to abandon their studies and return home that summer without completing their degrees. After returning to China, the "MIT 8" were mainly deployed along two tracks: the Navy; or in mining and railway engineering. They also took part in the development of telegraphy in China, as well as agricultural reform, business and other endeavors. Hence, they made vital contributions to China's modernization in several key sectors despite the obstacles.

Kwong Yung Chung is featured, first from right in front row, in this photo of the "Orientals" baseball team of the CEM.

Although they had studied only briefly at MIT, the training these men received at the Institute served them well, as recalled in a letter from Fong Pah Liang to his class in 1909:

The education received at the Institute proved a training of the mental powers, – memory, judgment, the reason, and will, – so that one can turn to any one of many lines of work and in a short time dovetail one's self into the position one has chosen. Should have desired a more liberal education, and regret that I did not even complete my course of studies at the Institute.

KY Kwong in reunion photograph of the CEM students in China, 1890. Thomas E. LaFargue Papers, 1873-1946, 2-1-4, courtesy MASC, Washington State University Libraries.

Kwong King Yang became known as one of the "fathers" of China's modern railways, and earned several medals for his contributions. He participated in building the first fully Chinese-engineered and -constructed railway in China, with a team fiercely determined to show skeptical Westerners that it could be done. As the Far Eastern Review wrote in 1913:

"When the construction of the Kalgan railway was entrusted to a Chinese engineer, many foreign railway builders shook their heads and prophesied that the line could not be completed without their assistance, otherwise it would be unserviceable and unsafe. They refused to believe that any foreign educated Chinese engineer could successfully push a railway up the Nankau Pass to Kalgan…They have done it." (Far Eastern Review, November 1913, p 201-202)

This engineering feat was considered a major coup in China at the time. As one Chinese official declared:

"When this line was first constructed, foreign observers all forecast a failure because they thought that Chinese engineers were inferior to Western engineers....Yet, within a short period this difficult and great project...has been accomplished....This not only brings honor to Chinese engineers of today but it will inspire those of the future." (Quoted in Wang, 1966, 468)

The achievements of these pioneering students were honored in the Twenty-Fifth Anniversary Book of the Class of 1884, and letters from Kwong King Yang and Sung Mun Wai were read at the reunion dinner. Tragically, three MIT men lost their lives in the infamous "Battle of Pagoda Anchorage" of August 23, 1884, the opening battle of the Sino-French war of 1884-1885, cutting short their promising futures.

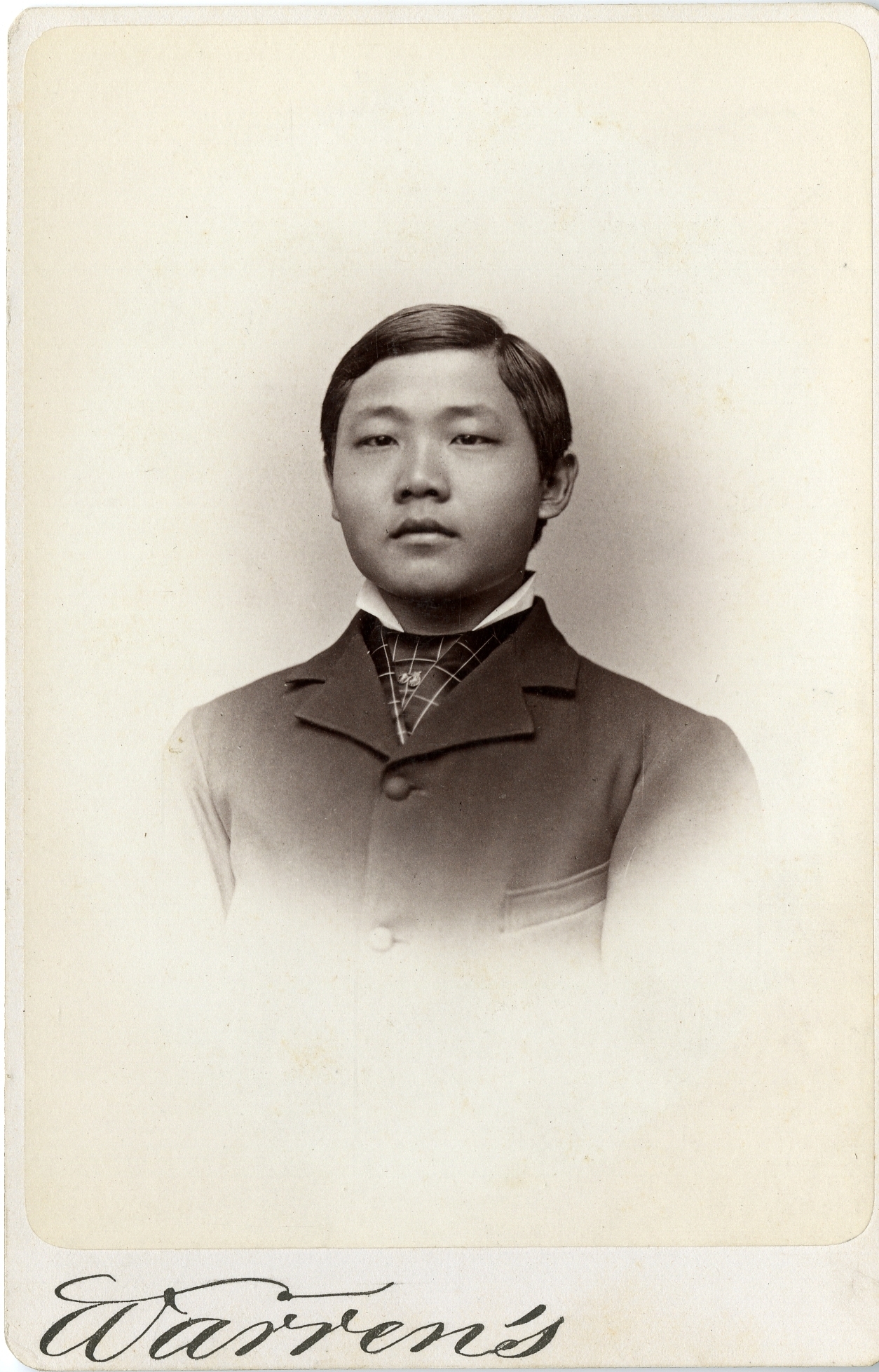

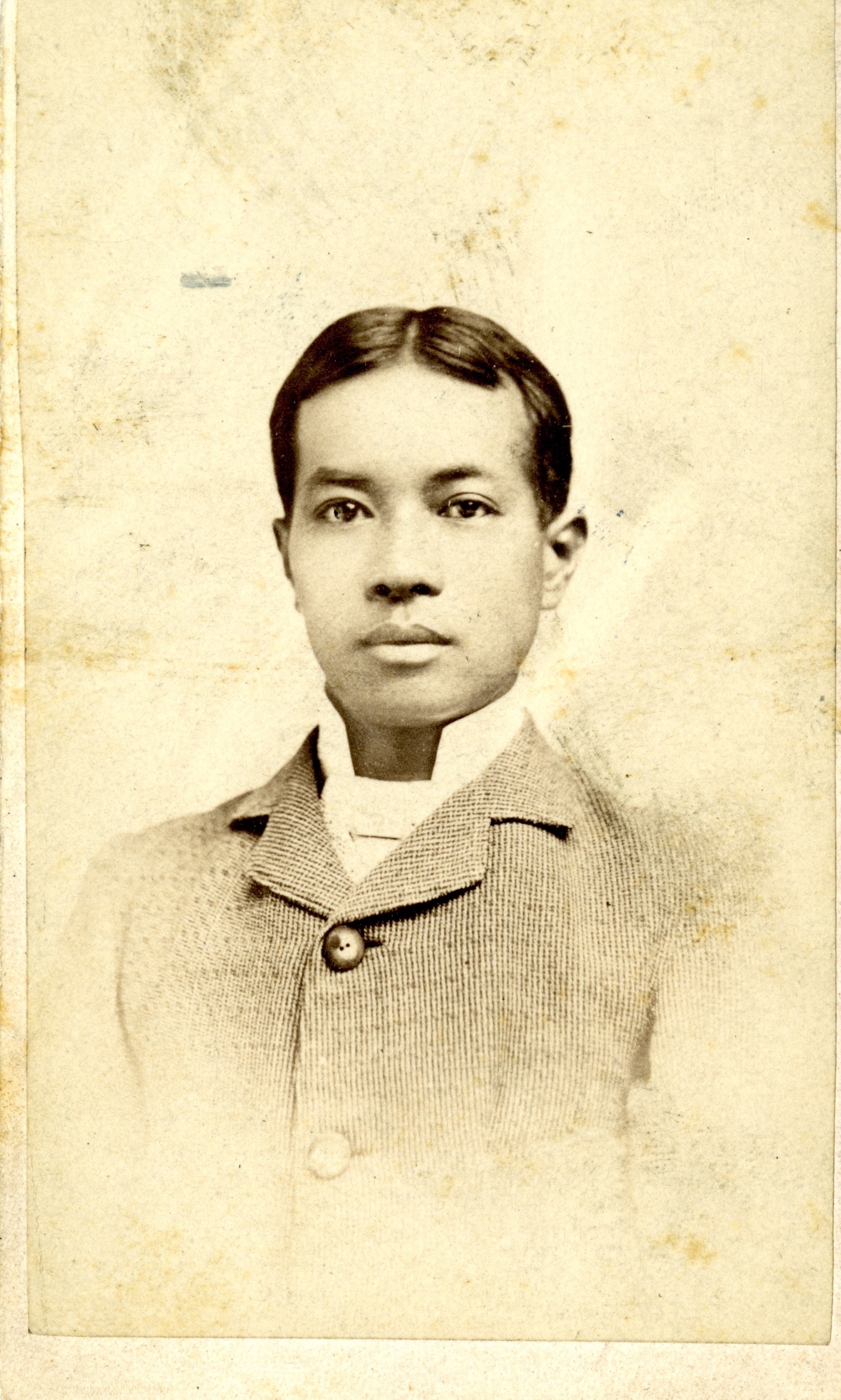

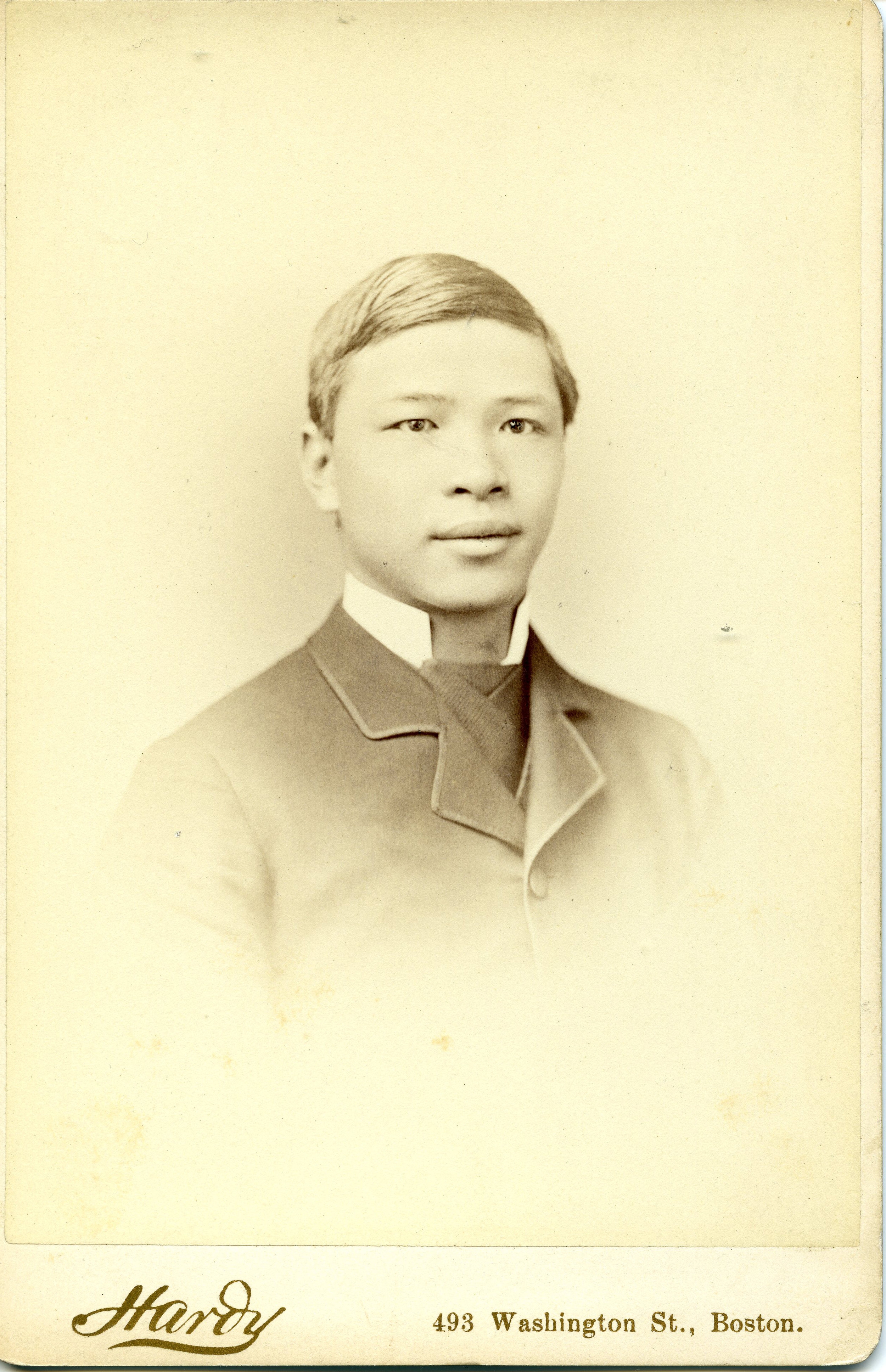

Image of Kwong Yung Chung courtesy of Williston Northampton School Archives. Image of Sik Yau Foke courtesy of Holyoke History Room, Holyoke Public Library. Image of Yang Seu Nam courtesy of Phillips Academy Archives & Special Collections. Images of Tyng Se Chung and CEM students used by permission of Manuscripts, Archives and Special Collections, Washington State University Libraries, Thomas E. LaFargue Collection. Images of Kwong King Yang, Sung Mun Wai and Fong Pah Liang courtesy MIT Archives and Special Collections.

Notes: The students attended ten different colleges: Yale 20, MIT 8, RPI 6, Lehigh 3, Amherst 1, Columbia 1, Harvard 1, Lafayette, 1, Stevens Institute of Technology 1, WPI 1. See Edward J. M. Rhoads, Stepping Forth into the World: The Chinese Educational Mission to the United States, 1872–81. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2011.

Sources: Yung Wing, My Life in China and America, New York: Henry Holt, 1909, 41. (First translated into Chinese in 1915) Information on the CEM is heavily indebted to CEM Connections, Edward J. M. Rhoads, Stepping Forth into the World: The Chinese Educational Mission to the United States, 1872–81. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2011, and Thomas La Fargue, China's First Hundred. Pullman: State College of Washington, 1942. Class of '84 MIT: Twenty-fifth Anniversary Book, 1909, esp. p. 43, MIT Faculty Records, Volume 3, 1879-1882, "An Appreciation of China's Railway Engineers," Far Eastern Review, volume X, no 6, November 1913 Shanghai and Manila, p 201-202, YC Wang, Chinese Intellectuals and the West, 1872-1949, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1966, Williston-Northampton Academy archives, Holyoke History Room, Holyoke Public Library, Phillips Academy Andover Archives and Special Collections, LaFargue Collection, Manuscripts, Archives and Special Collections, Washington State University Libraries. See also the Pioneer Valley History Network website on the CEM, and this feature.