Han Ho Huang (黃漢和 Huang HanHe)

by Dede Huang

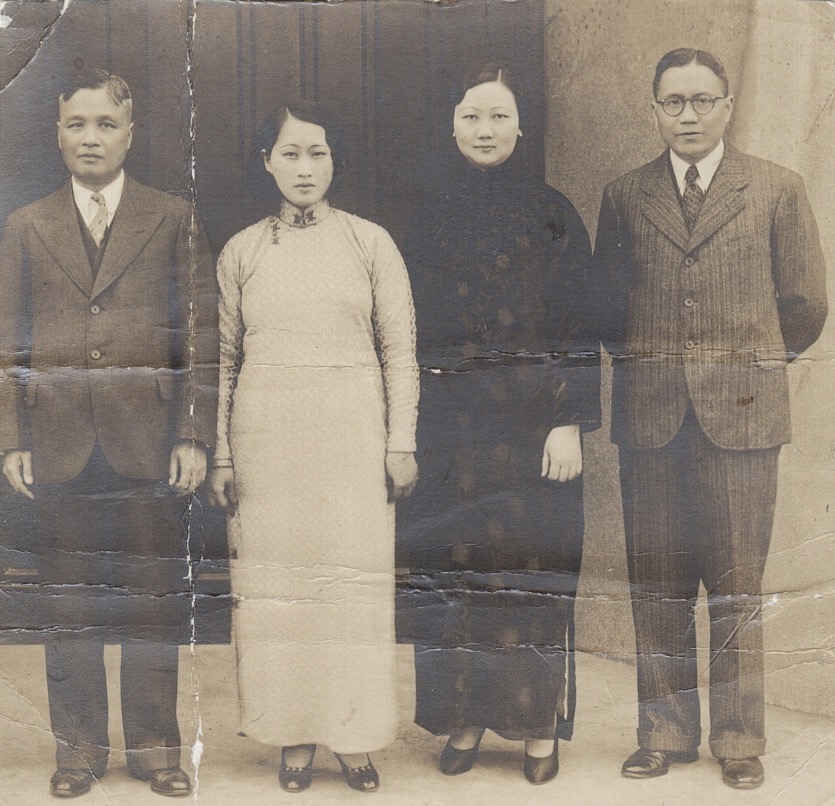

Han Ho Huang (far right) and wife Peggy Chiu, with older brother Han Liang Huang and second wife Zing Wei Tang, outside the American Community Church on Avenue Petain (now Hengshan Lu) in Shanghai in 1933. Han Ho and Peggy were active members of the church and from the late 1930s lived down the street. Photo courtesy Dede Huang.

Han Ho Huang (1893-1993, Class of 1917 Mining Engineering)

Mandarin pinyin Huang Hanhe, was born in the treaty port of Xiamen (Amoy) in 1893. He was the younger of two brothers whose father died in 1905, the same year that the imperial examinations were abolished. In these changing times, it fell to their mother - called Yu Koon (尤昆官 You Kunguan) - illiterate, with bound feet, and without wider family support, to scrimp and save to make their education possible.

Within a few years, the brothers entered the Anglo-Chinese College in Fuzhou, China’s largest mission school and the province’s most prestigious. There they distinguished themselves and from there they were sent to Beijing to try their mettle in new exams that offered a chance to study in the US. Yu Koon’s efforts were vindicated: in 1911 Han Ho’s brother, Han Liang, won a place in the 3rd Boxer Indemnity Scholarship cohort, and in 1913, Han Ho qualified as a Tsinghua (Boxer Indemnity) Scholar.

In 1914, Han Ho entered MIT on a path to a career in the mining industry, a sensible course given China’s ambitions to develop its industrial and military might. Enrolled in the Department of Mining Engineering and Metallurgy, he completed his studies in three years, writing an undergraduate thesis on “Concentration of an antimony ore - ore no. 2539.” Antimony was used to harden metals in the manufacture of arms, and China had large proven deposits of the element.

While at MIT, Han Ho was a member of both the Cosmopolitan and Chinese Clubs. In his final year - 1916-17 - he would have enjoyed the three-day festivities when MIT moved from downtown Boston to a new campus in Cambridge, as well as the school’s first commencement exercises. As one of sixteen students earning a BS in Mining Engineering and Metallurgy, he was in a decided minority among the 300-plus students awarded degrees on June 12, 1917. A peculiarity of the year was that MIT’s and Harvard’s engineering programs were briefly conjoined, conferring on Han Ho degrees from both universities. In spring of 1917 he was also required to register for the draft, noting his race as “Mongolian” and claiming exemption as an “alien.” MIT’s new campus did not yet have dorms, and his draft card indicates that he lived in the YMCA at 820 Massachusetts Avenue.

University of Xiamen staff record from 1926 indicating that Han Ho Huang was serving as interim head of the mathematics department. The record shows his MIT degree. Courtesy Dede Huang.

After leaving MIT, Han Ho worked briefly in Pittsburgh, finally in a position to do his duty by his mother and send money home. In 1918-19 he served as a graduate research assistant at the University of Illinois’s Engineering Experiment Station, where he was enrolled in the master's program.

He returned to China before completing his master’s degree, and it’s believed that he worked for a time in the Shanghai offices of the Han Ye Ping Iron and Coal Company, a proto-industrial-military complex that had begun as one of the Qing court’s efforts at modernization.

In the early 1920s Han Ho returned to Xiamen, where he joined the faculty of the University of Xiamen, a new institution determined to make a splash. He taught engineering and mathematics, and served as interim Head of the Mathematics Department in 1926.

He also met and married another Xiamen native, Peggy Chiu (周碧玉 Zhou Biyu, 1897-1964), the ninth of twelve children born to a Christian family with its own international credentials. The oldest was the first Chinese student to receive a doctorate from the University of Berlin, while another sibling married a Dane. Because of them, Peggy had lived in both England and Denmark, where she completed her schooling.

In 1929, the family moved with Yu Koon to Shanghai to live with Han Ho’s older brother Han Liang. The move appears to have marked the end of Han Ho’s academic career.

Han Ho and Peggy had three children: a son Moses (黃柏齡 Bailing, 1924-1929), who sadly died as a young child soon after their move to Shanghai, and daughters Mary (黃楓齡 Fengling, b. 1926) and Lulu (黃椒齡, b. 1933), who would as young adults settle in the US and Canada.

In 1937, the family fled to Hong Kong ahead of the Japanese invasion of Shanghai, but returned in 1939, remaining throughout the Sino-Japanese and civil wars. In the early 1960s, discouraged by the inability to secure appropriate medical care for Peggy’s declining health, Han Ho made plans for them to leave China, as their daughters had already done. To disguise their plans, he and Peggy walked out of their apartment on Avenue Pétain (now 衡山路 Hengshan Lu) as though only on a short errand. They left behind most of their belongings, including a near life-size portrait of Han Ho’s mother. It had been painted by one of Peggy’s cousins who had trained as an artist in France.

Unfortunately Peggy died in Hong Kong. Han Ho left alone for a new life in the US. He chose to make his home in Palo Alto, California, near his brother, where he lived to the age of 100.

Grave of Han Ho’s mother, Yu Koon (尤昆官 You Kun Guan, 1873-1933), soon after its refurbishment in 1962, Hungjao Cemetery, Shanghai. Photo courtesy Dede Huang.

Postscript

One of Han Ho’s last tasks before leaving China was to see that his mother’s grave in Shanghai was refurbished with a new tombstone. In his later years, a great regret was that he had left behind a family genealogy which listed out thirty generations of Huangs of the “Purple Cloud” lineage. While much of it was legend and hypothesis, it also contained the exact birth and death dates and Xiamen burial locations for four generations of Huangs preceding Han Ho’s generation.

Though lost to Han Ho, this homemade booklet sewn from brown paper and inked in several hands, found its way to me. Like Huang Zhong of 1827 who had spent many hours of toil to assemble the core of this genealogy, I have endeavored in my own way to reconstruct the lives of Han Ho and his brother Han Liang (my grandfather). With due respect, I offer this record of Han Ho’s life, another piece in the mosaic of that remarkable period of history when China opened up to the world and when, for a moment, everything seemed possible to China’s smartest men and women.

— Dede Huang (黃德莉), February 18, 2017, Hong Kong

Sources: Ryan Dunch, “Mission Schools and Modernity: The Anglo-Chinese College, Fuzhou”, in Education, Culture, and Identity in 20th Century China (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2001); Tsinghua Alumni Association website, > Nianji Lianluo > 1914; Tsinghua Wenku website > Xiaoyou Minglu > 1911 and 1914 pages; Technique, 1916, 1917 and 1919 yearbooks, Cambridge Tribune, Volume XL, Number 16, 16 June 1917, p. 5; “Directory of American Returned Students” pp. 11-12, in Who’s Who in China, Third Edition (Shanghai, The China Weekly Review, 1925); Alumni archives of MIT, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and University of Xiamen. Ryan Dunch, “Mission Schools and Modernity: The Anglo-Chinese College, Fuzhou”, in Education, Culture, and Identity in 20th Century China (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2001); Tsinghua Alumni Association website, > Nianji Lianluo > 1914; Tsinghua Wenku website > Xiaoyou Minglu > 1911 and 1914 pages; Technique, 1916, 1917 and 1919 yearbooks, Cambridge Tribune, Volume XL, Number 16, 16 June 1917, p. 5; “Directory of American Returned Students” pp. 11-12, in Who’s Who in China, Third Edition (Shanghai, The China Weekly Review, 1925); Alumni archives of MIT, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and University of Xiamen.