bringing "tech" to china

"…it is just because of this one weakness of ours [in scientific advancement] that we have to receive humiliating demands from our neighbors every now and then. Engineers, therefore, will have just as direct influence on the future of China as statesmen and diplomats; and it is only the successful engineer that will be our asset."

K.Y. Mok, Chinese Students’ Monthly, 1917

"A reunion of the [CEM] students in China, Christmas, 1890," Thomas E. LaFargue Papers, 1873-1946, 2-1-4, courtesy Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections, Washington State University Libraries.

building the nation

Beginning with the famous Chinese Educational Mission, launched in 1872, the Chinese government sent successive waves of students to the US for higher education, with the central aim of advancing China's modernization. Government scholarships were provided by a variety of sources, including: the Central Government or Board of Education; the Army, Navy, and Customs; and provincial governments. Most significantly, the Boxer Indemnity Scholarship Program, established in 1908, brought large numbers of Chinese students to American universities.

The government-sponsored students came to America with specific educational goals in mind. Under the "Self-strengthening" movement of the late 19th century, Chinese reformers promoted the acquisition of Western scientific, military and technical knowledge as the key to saving China from imperialist aggression. With the mounting crisis brought on by the series of unequal treaties forced on China, many students felt called to patriotic action. The need for engineers was particularly acute, and by 1914, engineering had become the favorite field for government students. In the eyes of many, engineering was not simply a practical skill, but a means of serving the nation.

In addition to the government-sponsored students, others came to the US on family funds, or through the sponsorship of missionaries, diplomatic officials, or other philanthropists. Self-supporting students, like MC Cheong (MIT Class of 1883), in fact formed the majority of Chinese students in the US after 1910, and a good number of eminent progressive families chose to send their children to MIT. The earliest were mostly the sons of merchants, bankers and compradores, who recognized the practical value of Western scientific and engineering education even when the conservative Chinese government did not. Families from this social stratum, many of them Christians, could be considered the "early adopters" of Western Learning (西學).

mens et manus

Dedicated to solving China’s pressing problems, MIT’s early Chinese students concentrated heavily in engineering and applied sciences. As early as 1914, MIT could boast the largest number of Chinese engineering students in the US, with 33 that year (followed by the University of Michigan with 23). Owing to the terms of their scholarships -- as well as US immigration restrictions -- the majority of the students returned to China, where they contributed to the advancement of science, engineering, manufacturing, commerce, agriculture, education, architecture, construction, and other sectors. The Chinese Educational Mission (CEM) students in particular are renowned for the role they played in modernizing China's navy, and in pioneering modern mining, railways, and telegraphy. A number of the students demonstrated their patriotism through military service, and four MIT men from the CEM lost their lives in important Chinese naval battles of the late nineteenth century.

CY Huang and SY Hung (Class of 1919), Technique 1920. Image courtesy MIT Archives and Special Collections.

defeating skeptics

The students were, furthermore, dedicated to demonstrating that Chinese could become first-class scientists and engineers, contrary to popular Western stereotypes of the era. Such stereotypes were propagated by influential Americans such as Dartmouth graduate, Charles D Tenney, a central figure in American educational initiatives in China. In a speech Tenney delivered at Dartmouth in 1907, he claimed that: "The sudden introduction of the modern sciences, which call for greater precision of statement than is natural to the Chinese, puts a severe strain upon the [Chinese] language" (my italics). In another speech, he further dismissed Chinese contributions to the history of science: "Until recently, the Chinese have taken no part in the extraordinary development of natural science." Such [mistaken] presumptions concerning Chinese "habits of mind," the structure of the Chinese language, or the absence of an indigenous scientific tradition, led many to be dismissive of the capabilities of Chinese scientists and engineers. German geologist Ferdinand von Richthofen, for example, declared that Chinese were incapable of mining the country's mineral resources without Western assistance, and others asserted the same for railway construction. The first generation of overseas-educated Chinese engineers, like Kwong King Yang, proved to skeptics their excellence in technical fields. (Kwong is pictured here wearing Jiahe Zhang 嘉禾章, 5th Order (1912) and Wenhu Zhang 文虎章 4th Order (1913) medals awarded for service to China.)

As York Lo shows, MIT graduates took the lead in establishing new engineering enterprises in China. Modeled on Stone & Webster, VF Lam (Class of 1916) and Earle Stanley Glines founded the pioneering Sino-American engineering firm Lam Glines & Co (允元實業) in Shanghai in 1919, for example, recruiting numerous Chinese MIT alumni to work for the company. According to Kuang-Piao Hu's (Class of 1919, Electrical Engineering) memoir, Lo writes, "civil engineering in China was dominated by Western firms and engineers at the time and Lam and his fellow returned students were determined to change that situation with their new venture." (See Lo's profile of VF Lam.)

King Yang Kwong, ca. 1914. Technology Review XVI.7, July 1914. Image courtesy MIT Archives and Special Collections.

PIONEERS

The early Chinese students were not only pioneers of modern science and technology in China, but also within a global context.

Technique 1917. Image courtesy MIT Archives and Special Collections.

For example, when MIT offered America's first course in aeronautical engineering in 1914, Chinese students were among the earliest to enroll. Hou-Kun Chow was the first student to complete the program, earning the first American MS in aeronautical engineering in 1915. Chow was part of a cluster of Chinese students awarded MIT's earliest degrees in aeronautical engineering, including: Charles Hsi Chiang (MS 1917), Wai Po Loo (MS 1917), Tsao Yu [Ba Yu Cao] (MS 1917), Shao Fung Wong (MS 1917), Wong Zen Tze (MS 1918), and Zhou Heng Huang (MS 1918). Indeed, Chinese students were so closely associated with the new study of aviation and aeronautical engineering, that the 1917 issue of the Technique mockingly wrote of Jerome Hunsaker:

"Why does he teach the Chinese aviation?"

"Oh, because they are the only ones who are foolish enough to believe he knows enough about it, and also they are the only ones nervy enough to take the course." (Technique 1917, 450)

Pioneers in the history of flight, these MIT-graduates went on to play central roles in developing Chinese aviation, which would prove crucial in the war against Japan.

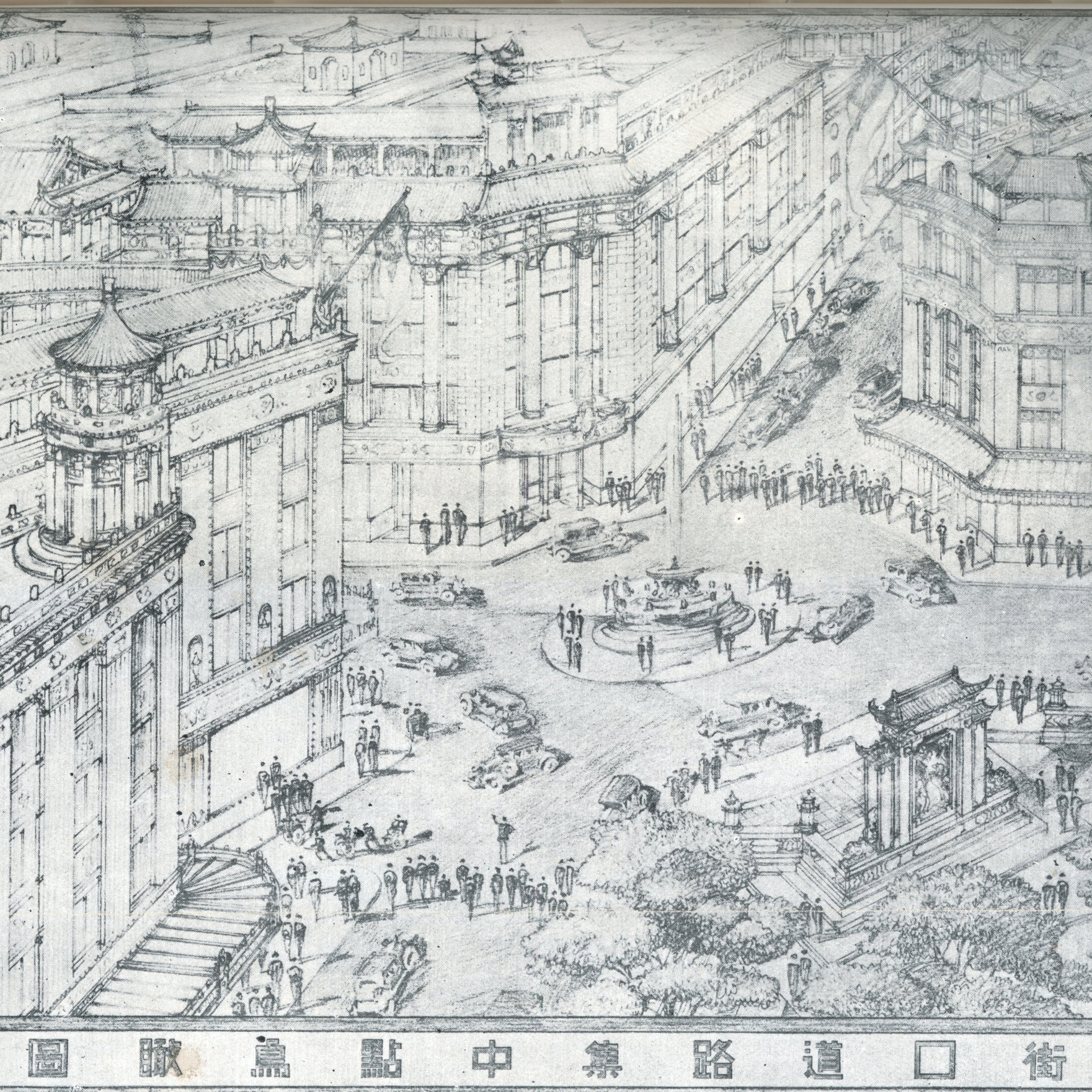

Architect Wong Yook-Yee's plans for the new Nanjing capital, 1929, Two Years of Nationalist China, 1930. Wong (Class of 1925, Architecture) served on the Nanjing City Planning Bureau with WY Cho (Class of 1917, Civil Engineering).

national reconstruction

In the late 1920s, with the establishment of China's new Nationalist Government in Nanjing (1927-37), "national reconstruction" became the central mission of the era, and engineers played the leading role in government-directed initiatives. MIT alumni Wong Yook Yee, W.Y. Cho, S.S. Kwan and others participated in the planning of a new modern capital, while engineers in diverse fields set about launching China's "second industrial revolution."

The 1920s also saw the rise of Electrical Engineering (Course VI) as the most popular course, by far, for Chinese students in the history of their first 50 years at MIT. Driving this popularity may have been the fact that Sun Yat-sen (China's George Washington) had strongly urged the electrification of China in his vision for an industrial China. Civilization, Sun had declared, was the "age of electricity." The MIT alumni were thus well poised when the National Reconstruction Plan promulgated by the Nationalist Government in 1928 made the electrification of China its central focus. As Bill Kirby has shown, electrification during this era came to be seen as "the people's salvation." The other top majors, mechanical engineering, chemical engineering, and civil engineering were equally vital to the project of National Reconstruction.

Educational reform, in particular the advancement of science and engineering education, was also a central mission of the era. In order to make the benefits of an MIT education more widely available to their compatriots, students and alumni undertook various translation efforts. For example, students prepared Chinese summaries of the MIT curriculum for their counterparts back home and led the way in the Chinese Students’ Alliance efforts to prepare a comprehensive bibliography of engineering reference works to be sent back to China. Beginning in 1929, MIT alum Prof. Ku Yu Hsiu (Electrical Engineering, Class of 1925, PhD 1928) led a group of Chinese students in translating the MIT textbooks for Electrical Engineering 600 and 601 into Chinese.

Above all, however, as Bill Kirby has written, China's engineers would prove to be "essential to Nationalist China's survival in an eight-year war against a technologically superior enemy [Japan]." (152)

Through their achievements and vital contributions to their homeland, the MIT graduates as "returned students" (歸國留學生) helped to promote the Institute's reputation in China. Many took on leadership roles or government positions. In this manner, the "Tech Gospel," in the words of the Boston Globe (December 23, 1917), was spread throughout China. Soon, many of China's leading industrialists, financiers, and businessmen aimed to send their sons to MIT, either on government scholarship or privately financed. MIT alumni thus became central in the formation of a new "technocratic" elite in Republican China. The "Tech Spirit" was further fostered through the establishment of MIT alumni clubs. The first Technology Club of China was formed in Shanghai in 1915, with monthly luncheon meetings, and clubs soon sprang up in other major cities across China.

Notes: It should be noted that some Chinese were strongly disapproving of the Western-educated "returned students," considering them arrogant, given to airs, and lacking in a true understanding of Chinese conditions.

Tenney was appointed President of Peiyang University in 1895, and later became Director of Chinese Government Students, before being appointed to the US consulate in China. In these capacities, he became a highly regarded expert on educational reform in China.

Sources: K.Y. Mok, Chinese Students' Monthly (CSM), March 1917, Volume XII, no. 5, 264, data on student majors, Chinese Students' Monthly (CSM) 10.1 and CSM 9.8, Technology Review XVI. 7, 1914, July, p. 472ff, George Bronson Rea, "An Appreciation of China's Railway Engineers," Far Eastern Review, volume X, no. 6, November 1913, Shanghai and Manila, pp. 201-207, CEM Connections, Edward J. M. Rhoads, Stepping Forth into the World: The Chinese Educational Mission to the United States, 1872–81. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2011, Thomas La Fargue, China's First Hundred. Pullman: State College of Washington, 1942, CL Wu, “The Importance of Chemical Engineering to China at Present," First Prize Essay, CSM vol 13, 1918, 382-389, SJ Shu, "Open Letter to Students of Engineering and Sciences," The Chinese Students' Monthly, Volume 9, No. 3, January 1914, 245-247, CC Woo, "Some Suggestions on the Preparation of Chinese Technical Students in the United States," The Chinese Students’ Monthly, vol. 16, no. 2, 1921, 168-172, Tenney, Charles Daniel, "Education Reform in China," An address delivered to the Dartmouth students, March 2, 1907, by President Charles D. Tenney, LL.D., Director of Chinese Government Students, Tenney, Charles D. The Papers of Charles Daniel Tenney. Hanover, N.H: Trustees of Dartmouth College, 2011. Internet resource, Tenney, Charles Daniel, “Speech on Education,” nd, Tenney, Charles D. The Papers of Charles Daniel Tenney. Hanover, N.H: Trustees of Dartmouth College, 2011. Internet resource, Shellen Xiao Wu, Empires of Coal: Fueling China's Entry into the Modern World Order, 1860-1920, Stanford, Stanford University Press, 2015, "Tech Training of Chinese Group May Mark the Birth of New Regime in Far East," Boston Sunday Post, November 6, 1910, "Future Admirals and Master Builders of Chinese Navy Are Trained at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology,” Boston Sunday Post, April 27, 1913, 10, AC.0597 Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Office of the President, Reports to the President, esp. 1912, p. 28 and 47, Bulletin of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, CSM 12, 1916, 355, Who's Who of American Returned Students (You Mei tongxue lu), Beijing: Tsinghua College, 1917, MIT Chinese Students Directory: For the Past Fifty Years, 1931, Technique 1917, p. 450, Aerial Age Weekly, vol 2, Sept 27, 1915, p 32, http://aeroastro.mit.edu/about-aeroastro/brief-history, MIT Senior Class Portfolio 1914, Kirby, William C. "Engineering China: The Origins of the Chinese Developmental State." In Becoming Chinese, edited by Wen-hsin Yeh, 137–160. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000, “Publicity in China: How our Chinese Students Are Helping to Make Technology Known in Their Native Land.” Technology Review v. 16, n. 8, Nov. 1914, pp. 564-566, The Tech, Sept. 27, 1915, Technology Review v. 17, 1915, 449, "Tech Gospel Spread by Every Tech Graduate: One Student in Every 15 Comes from a Foreign Country, China Leading the List with 48 – Reaching Better Understanding with South America," Boston Globe, December 23, 1917, page 13, Jiaoyu zhi qiao: cong Qinghua dao Mashengligong/Bridge of Education: From Tsinghua to MIT. Hong Kong: Cosmos Point Limited, 2011, American University Men in China. Shanghai: Comacrib Press, 1936.

!["A reunion of the [CEM] students in China, Christmas, 1890," Thomas E. LaFargue Papers, 1873-1946, 2-1-4, courtesy Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections, Washington State University Libraries. ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57bdab71e3df28e77a3cf28e/1474484338442-B4N11JHQ03H1SLNAXUHE/CEM+reunion+72.jpg)