Chinese exclusion:1882-1943

A precipitating factor in the recall of the Chinese Educational Mission was the tension between China and the US brought on by the rise of the anti-Chinese movement, which sought to curtail immigration from China. With its notorious slogan, "The Chinese Must Go!," this movement culminated in the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. Until its final repeal in 1943, Chinese Exclusion cast a long dark shadow over the Chinese American community, reaching even the students, despite their relative privilege. The context of Chinese Exclusion is important for understanding the achievements of the Chinese students and their experiences at MIT.

"Some of the Chinese students as they landed in San Francisco in 1872," Thomas E. LaFargue Papers, 1873-1946, 2-1-5, Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections, Washington State University Libraries. Used by permission.

the Chinese exclusion act

By the time that Cheong Mon Cham arrived at MIT in the late 1870s, economic competition and xenophobia were fueling mounting hostility against the "heathen Chinese," especially in the American West. Spurred on by demagogues, the anti-Chinese movement gained enough national momentum for Congress to pass the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, barring the entry of Chinese laborers into the US and prohibiting Chinese from naturalizing as US citizens. Eager to protect trade with China and access for American missionaries, the government stopped short of barring all Chinese, naming specific exempt classes ("officials, teachers, students, merchants and travelers for curiosity or pleasure") permitted to enter the US. Despite their privileged status, however, students from China felt profoundly the humiliation of Chinese Exclusion, and many came to view this discriminatory legislation as a grave injustice on par with the unequal treaties forced on China during this era. Linking the treatment of Chinese laborers in the US with China's degradation under imperialism, many students developed sympathy for their working-class countrymen. Some took action by volunteering in Chinatown, or going farther afield to perform welfare work among the [WWI} Chinese Labor Corps in France.

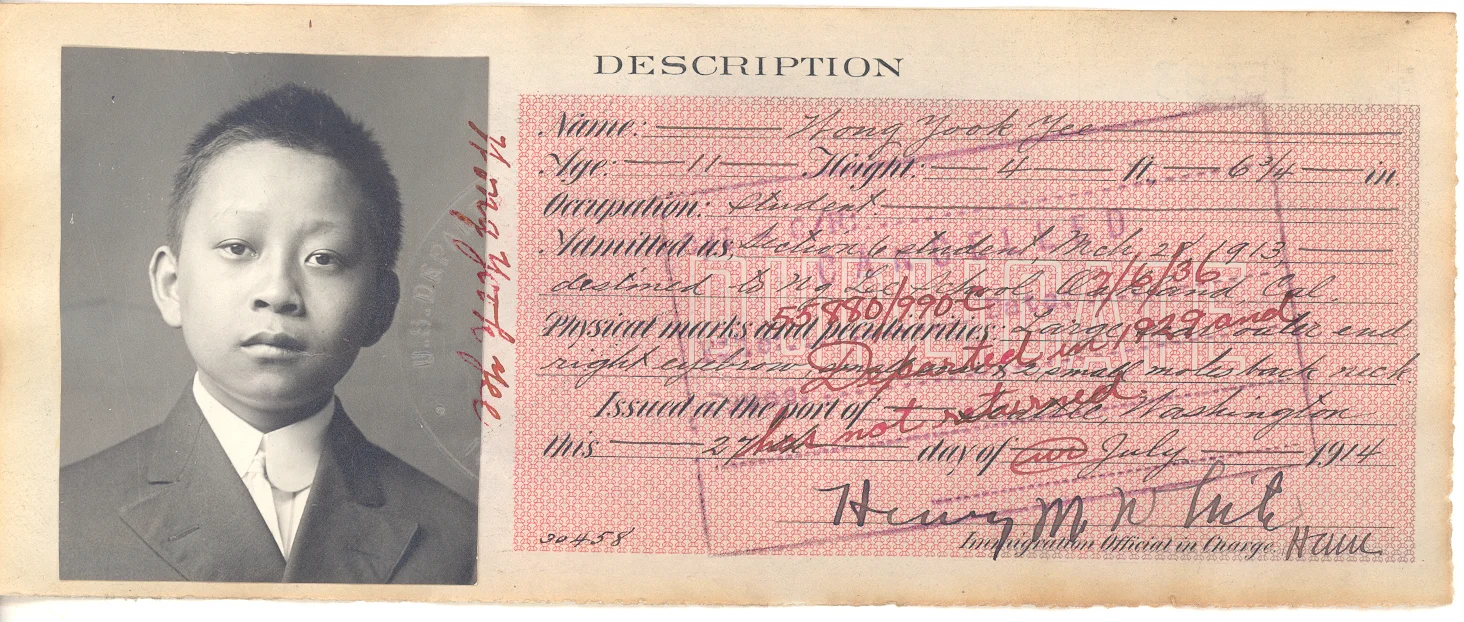

Y. Y. Wong medical certificate, 1913. Image courtesy Alexander Jay.

STUDENT LIFE UNDER EXCLUSION

In the wake of the Chinese Exclusion Act, the students from China faced stringent immigration regulations, being required to provide proof of their exempt status and medical clearance to enter the country. Students, furthermore, were not immune from harassment by immigration officials. In July 1904, for example, the group of 15 Chinese Government students brought to the US under the auspices of the Guangdong provincial government – including 6 MIT-bound students – were held up by immigration officials in Washington state before being permitted to proceed to San Francisco. The following year, the detention of four wealthy and aristocratic Chinese students by Boston immigration authorities sparked an international controversy. T.K. Tse (Class of 1908), one of the Guangdong scholarship students, visited them after their release to a Boston hotel, offering his support and sharing his own experiences that he faced in 1904. The Chinese Students' Alliance noted that the exclusion laws, or their enforcement, deterred many Chinese from seeking education in the US:

"No doubt many more Chinese students after the new learning would avail themselves of the excellent educational opportunities which this country offers, were it not for the fact that the Restrictive Immigration Laws are such that those who come have to come prepared for all manner of indignities and humiliations at the hands of the custom officials." (Meizhou liuxue baogao, 1905, 40)

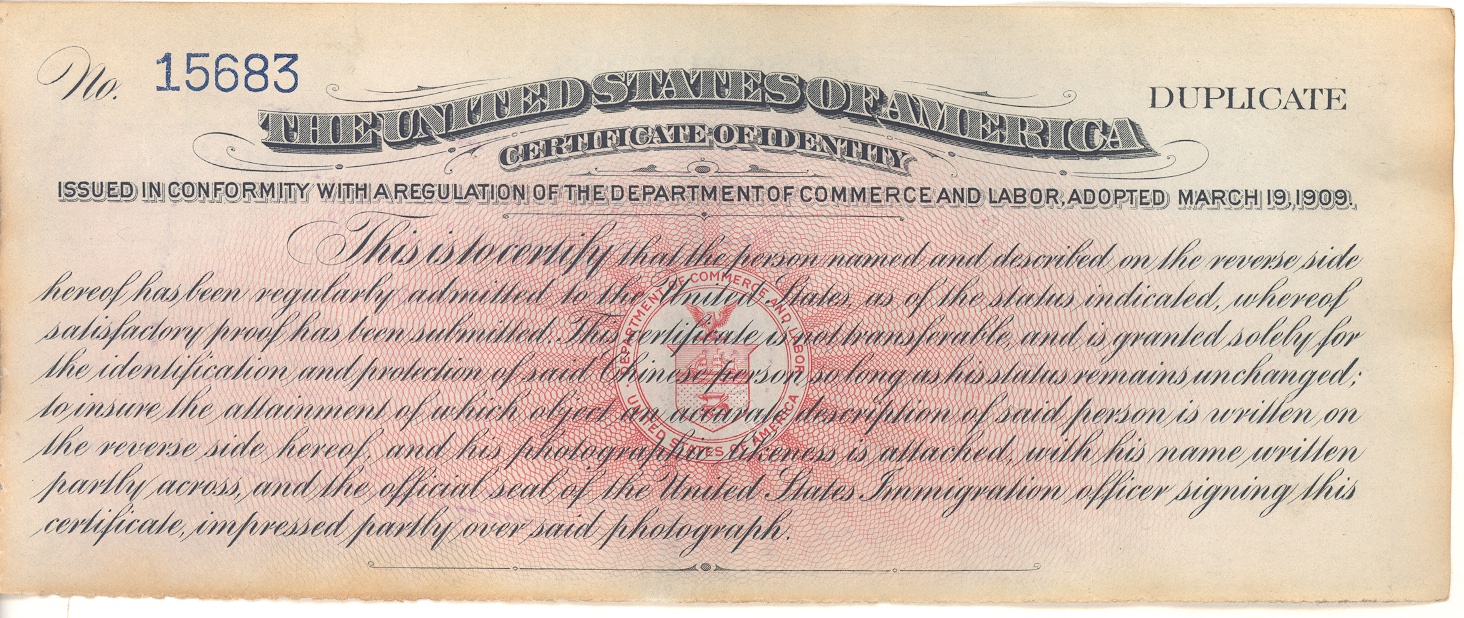

Examples of the types of documentation required from students come from Wong Yook Yee's Chinese Exclusion case file. The medical certificate (above) shows Wong cleared for hookworm and trachoma, while his identity certificate (below) shows his "Section 6" student status. Wong was a member of the MIT Class of 1925 and went on to become a renowned architect.

Y.Y. Wong certificate of identity, 1914, recto. Image courtesy Alexander Jay.

Y.Y. Wong certificate of identity, 1914, verso. Image courtesy Alexander Jay.

Immigration records show the difficulty some students faced on entering the country. Records for passenger arrivals on the SS Nanking, November 30, 1919 at San Francisco show that Zen Zuh Li (Class of 1922), line 1472, landed without issue. However, his friend Pau Ting Kwe (Class of 1923), line 1473, was landed on parole. Even more unlucky was Pay Kwun Lee, line 1474, bound for Urbana, Illinois, who was given a bonded landing and ultimately returned to China.

Lists of Chinese Applying for Admission to the United States through the Port of San Francisco, California, compiled 07/07/1903-01/07/1947; (National Archives Microfilm Publication M1476, 27 rolls. ARC Identifier 4482916); Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, Record Group 85; National Archives, Washington, D.C.

The mistreatment of the "exempt classes" – Chinese elites – was a major point of contention between China and the US, and one of the issues giving rise to a Chinese boycott of US goods in 1905-06, organized by merchants, gentry and students. The boycott prompted Massachusetts textile manufacturers and import-export houses to protest against abuses of the Chinese and lobby for immigration reform.

Under Chinese Exclusion, students were generally required to leave the country upon completion of their studies. Although the Boxer Indemnity Scholarship Program established by China and the US in 1908 did include provisions for students to undertake one or two years of practical work following their studies – for a total of six years in America -- the students knew that with few exceptions they must ultimately return to China.

Even returning home entailed difficulties. In June 1917, the Chinese Students’ Monthly reprinted a letter to “Students Intending to Return via Vancouver per Canadian Pacific Mail Steamers” advising students that: “For the transportation of Chinese Students through Canada from United States to Hongkong who are ticketed through via C.P.R. [Canadian Pacific Railway] and Vancouver, arrangements can be made for the entry of them and transportation through Canada without the deposit of the cash bond, without guard, and without surveillance on the following basis...” Students were required to obtain a certificate from their institutions substantiating their claim to student status, and to send this certificate with a signed photograph to the Chief Controller of Chinese at Ottawa. Such procedures led many students to complain that they were treated as common criminals.

PL Fong Class of 18814) and YC Kwong (Class of 1883) mocked as "Heathen Chinee," The Cauldron, 1877, p. 47. Image courtesy Williston Northampton Academy Archives.

Caricature of Tse Tsok Kai from MIT Technique 1908. Image courtesy MIT Archives and Special Collections.

"Grind" poking fun at Chinese script, MIT Technique 1914. "Modernized Chinese" is incorrectly represented as a primitive pictographic writing system.

Tse and Wen at Mining Summer School, MIT Technique 1908. Image courtesy MIT Archives and Special Collections.

The MIT archive provides glimpses of the ways that Chinese Exclusion shaped the experiences of the students from China. When Tse Tsok Kai and Wen Ching Yu joined the mining summer school in 1906, for example, they were interrogated by immigration officials on crossing the US-Canadian border with their group. Ten years later, in 1916, the department specially revived its mining summer school, which had been discontinued in favor of summer internships, to accommodate Chinese students. As the department explained: "the placing of Chinese students [in internships] is difficult, and, therefore, the summer school seems to be necessary for them." (Technology Review, 1917) Led by Prof. Locke, the unusual party that year consisted of six Chinese students and one American.

That this problem was not isolated, is suggested by an article published in the Chinese Students' Monthly in 1920, complaining of the lack of fair work opportunities for Chinese engineering students in America:

Caricature mocking "pigtailed" Chinese soccer players from MIT Technique 1920. Courtesy MIT Archives and Special Collections.

In general, the young graduates enter a certain industry and have full chance to learn everything about it from actual practice and experience. For some unknown reasons, this privilege has been denied the Chinese students in this country. Racial prejudice might be one of the drawbacks. (The Chinese Students’ Monthly Dec. 1920, 169, italics in original)

The revival of the mining summer school is only one example of the ways in which MIT, its faculty and administration, attempted to welcome the Chinese students and facilitate their education. Yet, the prevalence of anti-Chinese sentiment during this era inevitably affected the climate at MIT: as suggested by caricatures that appeared from time to time in the Technique. A prize-winning essay on "The American College Man" by Lee Ting Chen (Class of 1918, Chemistry), which was published in The Technology Monthly in 1918, brought to light Chinese student experiences of ignorance or condescension among their classmates. The essay urged Americans to "pierce through the great wall" of their isolationism.

Lasting Impact

Chinese Exclusion was not repealed until 1943, and new immigration laws passed in 1924 actually tightened the restrictions. The impact of this legislation on MIT can be seen in a number of respects: the relatively small number of US-born Chinese American students during these years, resulting from the immigration restrictions; the necessity of establishing special programs, for example in mining engineering or naval architecture, to accommodate the needs of students from China; and the fact that Chinese students were compelled to return to China upon completion of their studies and training unless they could establish themselves as teachers, diplomats or merchants, resulting in a loss of talent to the US.

Sources: Chinese Students' Monthly, June 1917, vol. XII, no. 3, p. 428, Chinese Students' Monthly, June 1910, vol. V, no. 8, p. 529, Mei Zhou Zhongguo xue sheng hui/美洲中國學生會. Mei Zhou Liu Xue Bao Gao, California: Mei Zhou Zhongguo xue sheng hui, 1905, Ng Poon Chew and Healy, Patrick J. A Statement for Non-Exclusion, San Francisco: s.n., 1905, Ng Poon Chew, "The Treatment of the Exempt Classes of Chinese in the United States: A Statement from the Chinese in America," The World's Chinese Students' Journal, Volume 3, World's Chinese Students' Federation, Shanghai, 1908, HS Hsin, "The Chinese Student at Tech," Technique 1915, 13-14, The Chinese Students’ Monthly volume 16, no. 2, 168-172, Technique 1927, 342, LT Chen, "The American College Man," The Technology Monthly, Jan. 1918, 25-27, 36, The Technique, 1907, p. 316, The Technique, 1908, 336, "Mining Summer School," Technology Review, January 1917, vol. XIX, no. 1, p. 49, “CHINESE SCHOOL CLOSES,” Boston Daily Globe, June 13, 1910; p. 5, Chinese Students' Monthly May 1910, vol. 5, no. 7, 419-431, Chinese Students' Monthly, 13.6, April 1918, 326-327, 357, The Chinese Students' Christian Journal, Volume 5.1, Nov. 1918, 63, Technology Review, vol. 16, 1914, 667.